The first time I came across something close to digital comics – although at the time I am sure I was not familiar with this specific term – was through manga scanlations circa 2004. Scanlation is a portmanteau of the words “scan” and “translation”, referring to unofficial fan work of scanning printed comics and translating them from their original language into other languages. During its golden age in the early 2000s, I would read scanlations through compressed files uploaded to the web and available for download free of charge. Despite the fact that scanlations clearly infringe licensing rights (since their modification and redistribution are, almost always, unauthorised by publishers and authors) they have had an undeniable role in the popularisation of manga worldwide. In a 2006 Japan Times article, Patrick Macias writes about how scanlators, driven by their love for manga, see their work as an effort to increase accessibility and popularity of the media among a larger audience. Without them I would not have had access to the Japanese comics that were never published in my home country, and maybe not even be as interested in reading and making comics as I am today.

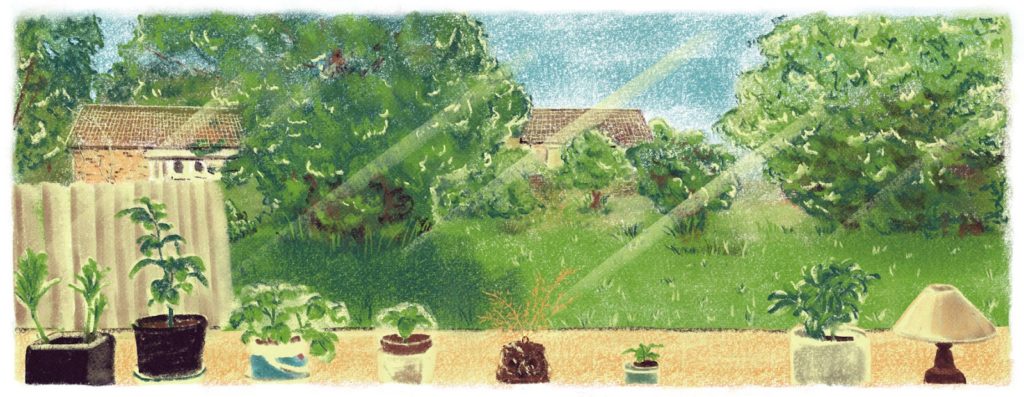

An important part of the scanlation experience was the development of the free software CDisplay Sequential Image Viewer, which, in comparison to standard image viewing software, optimised the experience of reading scanned pages offline on a CRT monitor. The CDisplay reads even sequential pages in compressed files and allows easy page navigation using the spacebar. No longer in development, this is a comics reading software that I definitely miss when reading comic eBooks in a web browser or in apps such as OverDrive. These other apps offer many tools to optimise the reading of words (different typefaces, background colour, etc.), but when it comes to comics, they do not offer a smooth reading experience such as CDisplay does.Back when I was devouring illegal scanlations of my favourite manga, I also noticed the rise of what we nowadays call webcomics. My earliest memory of reading webcomics was circa 2006 with Nana’s Everyday Life by Dan Kim, a parody of the manga and anime series Elfen Lied in cute drawings with not-so-safe for work content. Kim was clearly creating his comics entirely digitally with a pen tablet, which also awakened my interest for drawing digitally – something I was only able to achieve recently, after finally acquiring the software Clip Studio Paint. Unlike less-specialised apps such as Photoshop, Clip Studio Paint offers specific tools for drawing comics, including panel division, screen tones, and special rulers. What I struggled with the most in creating comics digitally was being unable to convincingly emulate the same results as if I was using analogue materials such as ink and brush, coloured pencils, and watercolour paints. But now I feel that I am getting better in producing digital images that are almost indiscernible from the ones I make with traditional media. Plus, drawing digitally makes it much easier to make corrections and alterations than in analogue work.

So, how do we define digital comics today? According to Mihnea Tufis in his doctoral dissertation on the evolution of digital formats for comics, “[…] the concept of digital comics covers both digitalised versions of originally print comics, as well as digitally native content. Native content itself can refer to webcomics, designed for the size of a computer screen (experienced in a browser) and the lately developing mobile comics, usually experienced on small-screen mobile devices, by means of dedicated applications. Tablets in particular seem to have a great advantage due to their screen size being approximately equal to that of print comic books.” On the other hand we have Jakob F. Dittmar’s article Digital Comics, in which he classifies digital comics into two main categories: web comics and downloaded comics. Published in 2012, this article did not predict our current reality in which most computer, tablet, and smartphone users are likely to have constant access to the internet. Even if I borrow a comic eBook from a library, there are cases in which I will not be able to download a file and read it offline, for instance in apps such as Adobe Digital Editions. Rather, I will only be offered the option to read the comic online using my web browser, and therefore this does not make the comic eBook a webcomic exclusively.

Another argument by Dittmar regarding digital comics terminology is that “[…] if these stories contain film – and/or audio-elements, they are no longer comics in accordance with the established definition of this class of media, but animated film or multi-media products.” I disagree with his affirmation, as I consider comics that contain audio or certain loop animations but still present the fundamental qualities of what we identify as comics (a sequence of images to tell a story, panel division, speech bubbles, etc.) to nonetheless still be comics. The same can be said about interactive films recently made available by streaming companies like Netflix. I would not call them “games” or “interactive multimedia products”. I would simply call them “interactive films”, as I still consider them to be films, even though they offer an additional quality in the experience of the viewer. Digital comics, as our usage and understanding of everything that is digital, has evolved and will continue to evolve in an urge to experiment and push the limits of our creativity.

In Japan, a country where I lived for nine years, the domestic market for both digital and printed comics is still expanding. A minority 40% of surveyed readers prefer reading on paper instead of on a screen, according to a survey by OshiKra in 2020; however, 52% of the participants affirmed not having a preference between print and digital, while only 8% answered to prefer digital comics. Moreover, 68% of the participants confessed having trouble with storage space for the printed comics they bought. It is important to point out that the digital comics market in Japan is not to be taken lightly, as it started gaining traction around 2014 and surpassed the sales of printed comics in 2020. But we must also remember that, as with eBooks bought from mainstream publishers, we get a temporary and conditional use of a comic, not a virtual file that is owned. Unlike a printed book, in which the object becomes our property, comic eBooks are functionally leased.

As for my personal experience, I started creating comics to be viewed digitally in 2019. Although my production consisted of using both analogue and digital tools, the primary goal was to post the comics on social media. After they got a good reception, I decided to make a printed version. This was not an isolated case, as many renowned artists also post their comics online to later print them as a book. Take, for example, Michael DeForge’s comic Birds Of Maine, which has its own dedicated Instagram account. Posting pages online throughout the process of creating a comic allows readers to stay engaged with the artist and their work. But even though the comic pages are still available to read for free on social media after the book was published in print by Drawn & Quarterly, I will personally prefer owning the whole story compiled in a well printed book rather than scrolling through social media posts.

Although I’ll most likely always favour printed over digital comics – mostly because of a personal preference for the book as an object over digital data – I do recognise the immeasurable importance of digital comics in my life. They offer advantages such as faster and cheaper distribution, take up no physical space and are therefore more mobile in comparison to physical books, and can be corrected and re-uploaded in case of publishing errors more efficiently than reprinting a book. But even though digital comics give opportunity for new forms of expression, such as insertion of loop animation, audio, and interactivity, we are still more or less bound to the rectangular format of the screens we use. Moreover, we cannot forget that paper also gives us a lot of possibilities. These could be pop-up three-dimensional pages, different types of bookbinding (including but not limited to accordion, scroll, and round formats), various paper thickness and texture, and the inclusion of different materials other than paper (such as textile, plastic, etc.). Let’s also not forget about the ability to quickly flip back and forth between non-adjacent pages, a task not so intuitive in most digital readers. However, these possibilities are not used very often in comics due to considerable increase in production cost and potential problems in distribution logistics. It’s easier and cheaper if books are in a standard format to optimise printing, transportation and storage.

Later in 2020, with the pandemic and the impossibility to participate in comic events in person, I continued to post my diary comics online, which has helped me grow my audience, boosting my confidence while working 100% digitally. This also helps me save money on art supplies – especially expensive Japanese paper and ink not always readily available in Europe – even though the initial cost of buying a computer and a pen tablet are significantly higher than standard analogue tools. Moreover, as I get more skilled using software to make comics, I can also optimise my process to produce faster and with better quality (for instance, having everything, from sketch to the final page, in the same file).

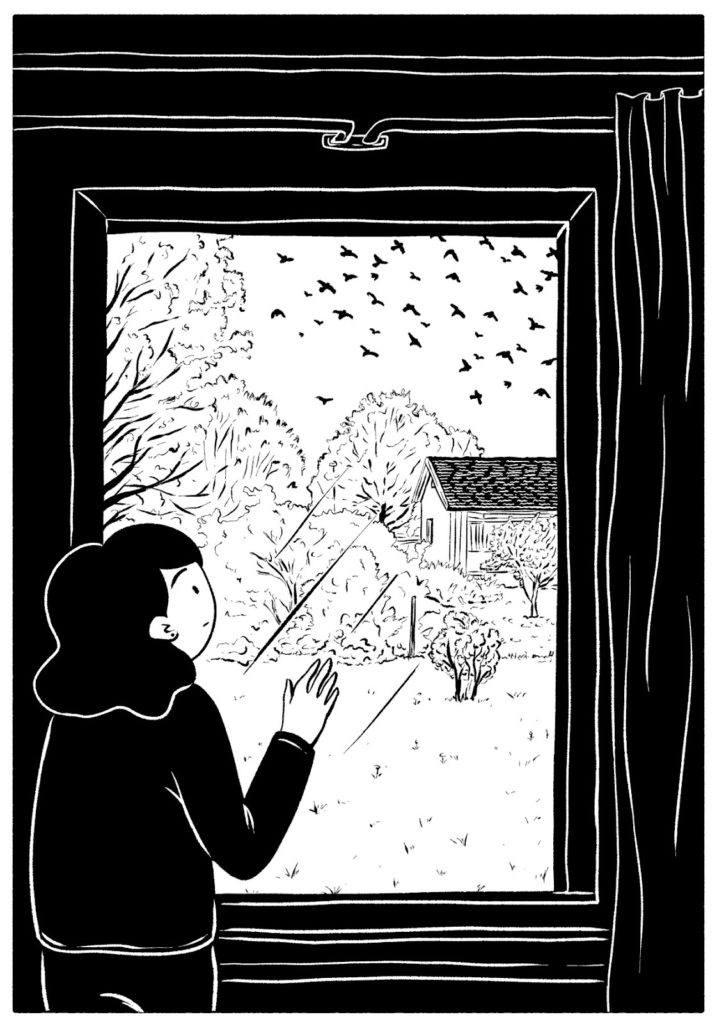

Another advantage of digital comics is the possibility of creating virtual communities, be it in a closed forum for cartoonists or the social media comments section. Until 2019, I was active in comics and zine events throughout Japan and Sweden, but in 2020 I was compelled to move to a village in the countryside. This physical isolation prompted me to look for ways to feel part of a community again in the online world, and in December 2022 I joined a cartoonist Discord server that has now become the Cartoonist Cooperative. The co-op offers a growing online database of comics of all sorts, private hubs for discussions, and we accept applications from cartoonists as well as from volunteers. All is free of charge, but members and volunteers are expected to periodically contribute with their time, knowledge, and labour. At first I was somewhat concerned about the commitment of joining the official cooperative, especially when I feel that I don’t have much to offer or even spare time to engage in helping others. However, these past months being part of this community have proved that my worries were nothing but misconceptions, as it has been a wonderful place for daily chat with other artists, a great platform to ask for advice regarding one’s work and practice, and an invaluable network of support for creating and promoting one’s comic. Moreover, the co-op Discord server and forum give us opportunities for feedback and knowledge exchange, for getting to know other people’s work, and a sense of connection so very needed in the lonely activity that creating comics can be.

Since moving to Sweden I was very fortunate to receive cultural incentives such as grants and art residency invitations that made it possible to work on my first ever long-form comic book. However, for someone who has been perfecting the art of telling short stories, I found myself quite lost in the process of creating a prolonged narrative. I didn’t know how to look for help and even though I insisted on trying to learn from my own mistakes there’s so much an inexperienced person can figure out by themselves. Here is where the co-op plays an important part in my journey, as in the past few months I realised that it could offer me a powerful set of tools for making better comics. This is only possible because there are so many individuals from all different areas willing to help everyone perfect their craft. These are amazing people who want to make the comics community a stronger and better place. Moreover, I feel the co-op is a safe space for me to grow as an artist, which is possible thanks to online connecting and sharing. I feel that we got each other’s back, and even if we’re in different time zones, we can always scroll back and check out chats once we’re awake!

My personal journey with digital comics started by reading scanlations alone in my bedroom, an activity that sowed a desire to start making comics and tell my own stories. As a hobby transformed into a profession, digital comics have been helping me find and be part of a community.

Julia Nascimento is a Brazilian illustrator and cartoonist passionate about autobiographical narratives and collaborations. While living in Japan for almost a decade she launched her artistic career and co-founded ToCo – the Tokyo Collective, a project that promotes visual story anthologies about the Japanese metropolis. Currently based in the countryside of Sweden, she has her work published in books and periodicals around the world such as The Japan Times, The Believer, and Bild&Bubbla. More at nsjulia.com and instagram.com/ns_julia.