Written by Charles Brubaker

In 1995, a brand-new webcomic appeared in the CompuServe forums, Kevin and Kell. Created by Bill Holbrook, who was already nationally syndicated with two comic strips On the Fastrack and Safe Havens, the strip featured a married wolf-and-rabbit couple navigating a world that didn’t accept marriages between a herbivore and a carnivore. The strip gained dedicated readers, and is still being produced to this day.

One of those early readers was David Allen, based in Thomasville, North Carolina. Allen was surfing CompuServe in order to find a topic for a tech column he was writing, and stumbled upon Holbrook’s strip. He was hooked. “I was totally amazed that it was on CompuServe and wasn’t syndicated,” Allen told The Business Journal in 2000. He enjoyed the strip enough that he emailed Holbrook asking if there were any book collections. To his dismay, there were none. Since the comic was already on the web there was no commercial appeal with the established publishers.

It was then that Allen approached Holbrook with a proposition: what if he were to publish the books himself?

Thus with a small investment and a contract that was written without a lawyer (Said Allen, “I’m sure they’d break out in hives because it’s in plain English.”), David Allen formed Plan Nine Publishing in 1996 with the singular goal of publishing Kevin and Kell in print. Allen named his company after Ed Wood’s low-budget masterpiece Plan 9 from Outer Space. “My wife and I joked that we were doing this business on an Ed Wood budget,” Allen said, and the name stuck.

“Dave basically started Plan 9 to get Kevin and Kell books into print, and that was always his bread and butter, but he was eager to get [other webcomic creators] involved if he could.”

John “The Gneech” Robey

The first Kevin and Kell collection, titled Quest for Content, was released in 1997, and with that, webcomics would enter the print market. Within three years, four more book collections would be published. It was around that point Plan Nine would look to expand their output with other creators. “Dave basically started Plan 9 to get Kevin and Kell books into print, and that was always his bread and butter, but he was eager to get [other webcomic creators] involved if he could,” recalled John “The Gneech” Robey, whose webcomics The Suburban Jungle and NeverNever were published by Plan Nine. “He was a big fan of the comic strip as a medium, and my impression was always that he felt having print collections lent webcomics an air of authenticity, putting them on a similar footing to newspaper comics, which were still a big deal at the time.”

By 1999 Allen had signed on nine more cartoonists, including Robey, Thomas K. Dye (Newshounds), Dana Simpson (Ozy and Millie), and Jeffrey Darlington (General Protection Fault). “I submitted sometime in 1999, which would be about a year into [Ozy and Millie’s] run,” recalls Simpson. “I didn’t have a big audience, but I’d gotten a big boost from swapping comics with Bill Holbrook that April Fools’ day. I felt like things were happening. And of course Plan Nine was Bill’s publisher at the time. I asked Bill if he thought I had a chance and he encouraged me to submit.”

“Plan Nine had already published a handful of books for Pete Abrams [creator of Sluggy Freelance] and Bill Holbrook and was looking to pick up some additional clients.” recalled Darlington. By 2000 the company had published more than 30 books, and it had grown to the point that Allen left his job as a systems engineer at Financial Computing to focus on Plan Nine full-time.

According to The Business Journal, 98% of Plan Nine’s sales were purchases made by customers through its website. Because of that and their small initial print-run of around 2,000 or less, this allowed Plan Nine to get a 70% gross profit margin, with artists getting a 20% royalty, four times the industry standard according to the Journal. The profit share was especially noticeable for Holbrook, who had two On the Fastrack books printed through traditional publishers in 1985 and 1991. “Plan Nine gave me a much larger share,” said Holbrook.

Finding printing facilities that could do small-press runs proved to be a challenge, however. Allen primarily dealt with a print broker in Virginia Beach who would find facilities that accepted smaller print jobs, which would allow small runs of their books to be made for a decent price. This arrangement led to printing quality varying widely. “They were always changing printers and trying to get the most affordable printing,” said Simpson. “The first Ozy and Millie book came out in January 2000, and the first printing of it had this issue where the glue was faulty and the covers would fall off. That got addressed, but the print quality varied a whole lot over the years.”

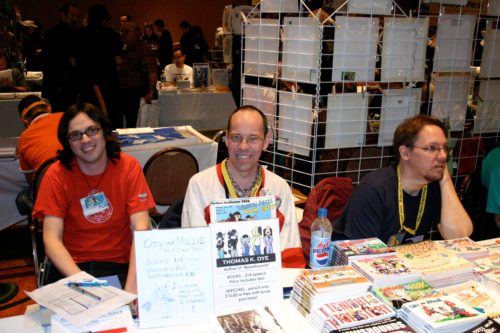

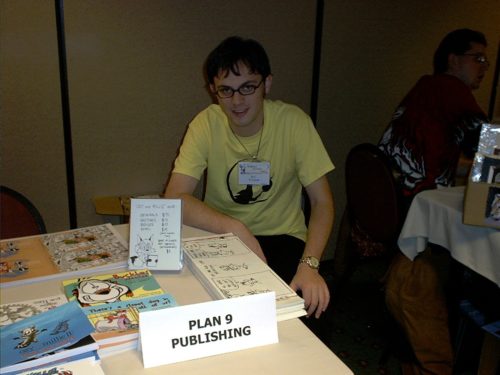

Plan Nine was always a small operation. Much of the administrative work was done by Allen, although creators published with the company would volunteer their time when possible, such as Thomas Dye. “In 2000 I became a dealer at Further Confusion [a furry convention in San Jose, California] as I was living in the Bay Area at the time,” said Dye. “Once David Allen started publishing Newshounds books I offered to sell Plan Nine books at Further Confusion, and he was amenable to that. So I got a whole host of boxes of Plan Nine products, and thus began an arrangement that continued for at least four more years!”

Jeffrey Darlington, who was living in Greensboro, just north of Thomasville, would also volunteer his time. He recalls laying out the third General Protection Fault book at Plan Nine’s offices when Allen was buried with work. He would also find himself providing technical assistance for the online order form originally built by Bryan McNett, whose Big Panda service provided web hosting to the emerging webcomic scene in the late ‘90s, most notably Sluggy Freelance. He was also, according to Darlington, “notoriously unresponsive and difficult to get a hold of,” leading to McNett and Allen having a strained relationship.

McNett’s unreliability most notably reared its head when Allen had a tight deadline to get new books added to the order timeframe. “David turned to me for help, as I was a fledgling web developer at the time,” recalled Darlington. After managing to get McNett to give him access to the page source (“I will keep my comments on the page’s code quality to myself.”) Darlington managed to hack in new books to the form. This incident prompted Allen to purchase a storefront software for the site, which Darlington helped install and configure.

The only other employee at Plan Nine, besides Allen and his wife, Lisa, was Vik Leafe, who helped out behind the scenes, mostly in conventions. “[Vik] helped man the table when we needed a break,” Dye recalls. “He also helped with finding books, setup/teardown, moving boxes, the usual […] I don’t know how David Allen found him. One day he was just there.”

While Plan Nine’s main focus was always webcomics in print, the company would begin publishing collections of existing newspaper comics, initially with Holbrook’s two syndicated strips, but later expanding to include Mark Parisi’s Off the Mark, David Gilbert’s Buckles, and Jim Meddick’s Monty. The company would put out Plan Nine Publishing Christmas Annual in 2000, featuring all new comics from their creators. In 2003 the company put out its first non-fiction book, Black Box Voting. Co-written by Allen and Bev Harris, the book was marketed as an “expose” on the world of electronic voting machines. In 2005 Plan Nine also published a memoir, I Lived With My Parents and Other Tales of Terror by Mary Jo Pehl, best known for her appearances in Mystery Science Theater 3000.

David Allen expressed optimism about Plan Nine’s growth when interviewed by The Business Journal. “Based on sales for the first two months of 2000, Allen predicts revenue of $250,000 for this year. He says that 2001 may top $1 million,” the article said. If the company really did reach that amount in 2001, it would have been their peak.

When Dana Simpson was asked what the turning point for the company was, she argued it would be around 2003, when David Allen’s wife, Lisa, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. “For reasons I think we all could understand, that became a bigger priority in his life than publishing books of webcomics,” she said. Thomas Dye also pointed to the publication of Black Box Voting as another factor in Allen’s wavering interest with Plan Nine. “He became more interested in voting machine anomalies than the publishing business,” said Dye. John Robey, meanwhile, pointed to the challenging nature of running a small business. “Plan Nine was launched at the height of the dot-com boom when there was a lot of creative energy and excitement and money to spare, but the final fate of every boom is that there is eventually a bust. Weathering that bust is the real test.”

“Plan Nine was launched at the height of the dot-com boom when there was a lot of creative energy and excitement and money to spare, but the final fate of every boom is that there is eventually a bust. Weathering that bust is the real test.”

John Robey

Things did not improve when 2004 rolled around. Simpson recalled that her books would be frequently out of print, with Allen increasingly delaying the reprinting of existing titles. Royalty checks also began to slow down at this point. “I needed that money, however paltry, since often there were no books for anyone to buy,” she recalls. Thomas Dye also faced frequent delays with his books, which hampered his convention presence. “Twice a new Newshounds book I’d wanted to sell at Further Confusion wouldn’t show up, and I’d have a miserable time at the table with no new product to sell. Be aware I was doing this of my own volition – I was even paying the dealer’s attendance fee myself!”

For Dye, the final straw came when Allen worked out a deal to syndicate a full page of webcomics on a weekly basis to college newspapers. “We discussed it and I agreed to assemble the necessary comics as needed, and upload them. I uploaded about six months’ worth of comics in advance. Six months later, I tried to upload the next six months’ worth… and the site was down.” Dye later found out that the project had long been canceled and was not informed by the higher-ups. Frustrated by his experience, Dye made the decision to self-publish his next collection, which won an Ursa Major Award.

Dana Simpson also began looking into self-publishing after her friends informed her of a fledgling print-on-demand market. “They pointed me to Lulu.com, and I looked at it, and…print-on-demand! Books can’t be sold out!” Wanting to get a new book out in time for Christmas 2005 she quickly assembled Tofu Knights, the first Ozy and Millie collection not to be published by Plan Nine.

This did not sit well with Allen. “He was like, ‘I’m your publisher, how could you.’ And I was like, ‘you said you’d make the holiday season, I’m sorry, I had to take matters into my own hands, you keep missing deadlines and breaking promises.’” Allen sold the remaining stock of Ozy and Millie books to Simpson (about $400 worth) and ended their professional relationship. “I’ve never wished Dave ill, and I felt bad that he was hurt by that, but, sadly, I think it was pretty obviously my only option by then.”

The remaining creators would struggle to get in touch with Allen. “After I moved away from North Carolina in 2006, all my communications with Plan Nine became sporadic,” said Darlington. “I emailed David multiple times about the status of various projects, especially the fifth GPF book which, at that time, was still in development. I don’t recall if I attempted to call him directly or not, but if I did, I think the number came back as disconnected.” When Darlington’s contract with Plan Nine was up for renewal, he let it expire due to a lack of communications. “Needless to say, I was frustrated and exhausted by the silence.”

Kevin and Kell, their flagship title, would leave Plan Nine as well. The final book from the company, Yo Mama, was released in 2007. In 2008, the Plan Nine website was empty except for this text: “Plan Nine has gone on hiatus for retooling and transition to new owners. Please check back with us Sept 1st, 2008. Thanks for your support!” September 1st came and went with no sign of life from the company. Then the website went offline, and that was the end of Plan Nine Publishing.

Kevin and Kell would continue publication under Moonbase Press, set up by cartoonist John Lotshaw to take over the vacuum left by Plan Nine’s demise. He also reached out to Darlington and talked him into publishing the next GPF book under the Moonbase banner. “Although I felt a bit burned by [Plan Nine’s] disappearance, I was hopeful to keep the book line alive, especially since I had already done the lion’s share of the work in setting up the fifth book.” However, in a case of history repeating itself, his communications with Lotshaw began to dwindle as well. “Eventually, I received a ‘Mea Culpa’ e-mail in which John apologized profusely for his silence.” Lotshaw would pay the estimated remaining royalties (his records were incomplete) and shipped the remaining stock of both the Plan Nine and Moonbase books to Darlington.

By the late 2000s, more and more webcomic creators began exploring self-publishing options, as print-on-demand companies such Lulu, CreateSpace (now Amazon KDP), and IngramSparks began to proliferate, allowing creators to put out books without having to worry about running out of stock. Webcomic creators gained a further boost when Kickstarter was launched in 2009. A platform that lets people crowdfund their projects, creators can now solicit funds directly from their readers to have their comics printed, giving them further control without having to deal with unreliable publishers.

General Protection Fault ended its print run with the collapse of Moonbase Press, but many former Plan Nine titles managed to live on via other means. Dana Simpson would self-publish further Ozy and Millie collections via Lulu, even reprinting earlier strips from the Plan Nine run into new, expanded collections. Ozy and Millie gained further circulation when Andrews McMeel, capitalizing on the success of Simpson’s Phoebe and Her Unicorn, published two “best of” collections in 2018 and 2021. Bill Holbrook turned to Lulu as well when he took over publishing collections of his three strips through the platform, which continues to this day. Thomas Dye brokered a deal with FurPlanet to take over publishing the Newshounds (and his later Projection Edge) collections. (Attempts were made to contact David Allen for this article, but were unsuccessful.)

The webcomic landscape (and the internet in general) has changed drastically since 2008, but one constant is that there are still demands for webcomics to be collected in print. Mainstream publishers have taken note. Webtoon, a South Korean-based webcomics platform, has seen success in marketing their flagship titles for print. “As demand for graphic novels remains strong, especially in middle grade and YA categories, publishers are turning to popular digital platforms to scout for turn-key titles,” wrote Shaenon K. Garrity in Publishers Weekly.

Thomas Dye summed it up best when explaining Plan Nine’s impact on the world of webcomics: “Plan Nine started out as very ambitious and should be commended for seeing the potential in printed comic strip collections. It’s true most people wondered about the point of print collections of something that was available on the net. But it turned out people wanted something they could have in their hands. Books ended up still being important to people!”

Charles Brubaker is a cartoonist and animator. His cartoons appeared in publications such as MAD Magazine, SpongeBob Comics, and many more. He has created comics “Ask a Cat”, “The Fuzzy Princess”, and currently “Lauren Ipsum”. He lives in Tennessee.