Written by E.B. Hutchins

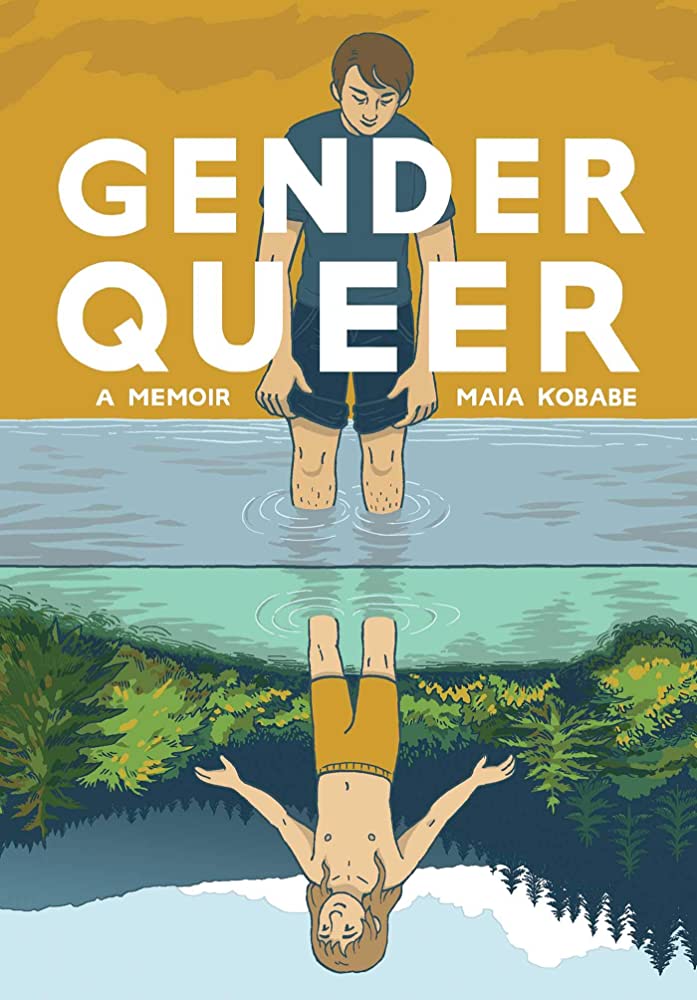

“This is what they were trying to sue them over?” was a question that hovered over my head during one of my weekly trips to Barnes and Noble. I sat in the cafe with my usual order (turkey and chipotle sandwich, sea salt chips, strawberry & creme frappuccino, and a chocolate chip cookie) flipping through the pages of Maia Kobabe’s (e/em/eir) memoir Gender Queer. The memoir is vulnerable and open in its telling of Kobabe’s life as a nonbinary person and feels right at home with other memoirs like Allison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Kate Beaton’s Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Lands, and Lucy Knisley’s Kid Gloves.

However, if you’ve been a part of the comics industry, industry-adjacent, or just a comics fan, you may have heard about Maia Kobabe’s memoir and the lawsuit that followed its publication. If you haven’t, the TL;DR of the case is that the state of Virginia was so offended by some of the contents in the book that they deemed it to be obscene for children. The offensive contents in question included pages where Kobabe described eir experiences with periods, depictions of period products and blood, Kobabe’s dysphoria, as well as some sexual experiences that don’t feel that out of place for teenagers/college-aged people who grew up in the 00’s and 10’s.

Kobabe’s unflinching honesty is what the memoir genre is built on, and marginalized voices keep the genre fresh. It getting banned isn’t shocking. Nor is being on a banned book list a death sentence in publishing or for future prospects. However, having an entire state bring down a sledgehammer on a book hasn’t happened since the Jim-Crow era with Garth Williams’ book The Rabbits’ Wedding.

Gone are the days when banned books were just about pearl-clutching PTA moms not wanting their sweet 12-year-old boy Tommy to see titties. Now, book banning looks like court cases and felony charges just for having work that features LGBTQIA+ people and openly talking about racism being bad. What happened?

In a word: Fascism.

This is nothing new when it comes to fascism, however it’s best to ask when the most recent version of it rose to prominence. In this case, it really started to kick up in 2017, after Trump took office.

In 2017, Charlottesville happened, the first openly neo-Nazi event to hit mainstream media in decades. That event segued to the neo-Nazi wing of the party making deeper and deeper inroads into all aspects of American politics. This has led to now over 300 anti-LGBT legislation bills in the works like the Tennesee Drag ban, Florida’s Don’t Say Gay Bills, Oklahoma’s ban on gender-affirming care, the repeal of Roe v. Wade, and numerous racist bills including one that brought back Jim Crow-era discrimination into Mississippi.

But what does this have to do with books?

The suppression of free speech and censorship of dissenting ideas are key features of right-wing authoritarians, and book banning is one means by which they attain and maintain their hold on power. By limiting access to information and different voices, fascist regimes aim to shape public opinion and reinforce their own ideologies.

Getting back to Gender Queer, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to tell you that queer work, work that addresses racism, or work that speaks on women’s issues (like Comics For Choice) would be deemed unacceptable by the modern GOP. They have the capital and the legal system to enforce these bans for all books being published, and they’re not going to stop at books already released. They may even start looking at submissions in publishing houses across the country.

So what are we supposed to do as book lovers and bookmakers?

Allow me to get personal for a second.

From the funnies I read every weekend at my aunt’s house as an elementary school kid, to the Sonic The Hedgehog fan comics I made as an awkward middle schooler, to the shonen battle manga like Bleach that defined my deeply insecure high school years, to the American indie comics like Giant Days that helped me get through college, reading and making comics has been a cornerstone of every major chapter of my life.

To put it simply, I have dedicated a large portion of my life to loving and being a part of this medium. However, I’m scared of what the future of publishing looks like for everyone.

As I’m putting the finishing pieces together for my query letter for what I hope to be my debut graphic novel, that fear comes over me. What am I going to be on the receiving end of? Will my work fly under the radar of the far-right’s media machine? If published, will it only cause some dust-up or will it be a national story? Will my life be ruined by this? How many of my accounts will be hacked because of this? Will I have to move?

My work, which is a massive love letter to shonen battle manga and lesbian culture, won’t just have to contend with “chuds” or basic homophobes if it reaches a broad audience, it will have to contend with an entire machine that has already tasted the blood of Don’t Say Gay bills and drag bans and gender-affirming care bans. A machine that, if they win the presidential election and control of Congress in 2024, could pass laws that make publishing my book illegal in this country like they are trying to do in Tennessee.

So this is what we can do.

Stay true to ourselves

When I think of all the new work I’ve read over the past 10 years, I’ve noticed a burst of different voices in comics, both in the mainstream and independent markets. This has led to increased mainstream representation with more nuanced depictions of BIPOC, LGBT+ people, religious minorities, and disabled people. This work has been vital and affirming for so many, so don’t stop making it, despite the opposition to it.

You’re not alone in this: comic creators have been making challenging work for a long time. Maus, Blankets, Saga, This One Summer and Dragon Ball all faced bans and legal challenges. More recently, Iron Circus Comics had difficulty finding a printer that would print Evan Dahm’s The Harrowing of Hell.

Join the Cartoonist Cooperative

At time of writing, the collective has hundreds of members from all different parts of the industry and the world. There’s power in numbers, and we should stick together. After all, this website promotes our comics and hundreds of people are able to answer questions, help crowdfund projects, and compile resources through the forum and Discord server. I often think about organizations like the Communications Workers of America and the strategies used for the HarperCollins strike when it comes to great examples of collective action.

Rebel Quietly

In the coming years, we may have to learn how to skirt the language that can get us prosecuted. This tactic has been a part of marginalized cultures since the founding of this nation. From flagging in LGBT+ spaces to green books for black folks, we have always had to hide in plain sight and make maps of where we would be safe.

I recall the way that a number of comics worked around the Comics Code in the 50s until the early 2000’s. A number of artists worked in underground spaces, collaborating with comics shops to make subversive material during the 60s. In the 70s, comic lovers kept comics that violated the Comics Code alive at conventions. Nowadays, we have the internet. Speaking of…

Build archives

Despite our work being at risk of being banned through mainstream channels, we still have the internet as a safe place for us to share and sell our comics. We have itch.io and a multitude of ways to sell comics and PDFs on the internet. While I’m aware that reading digital comics is not everyone’s cup of tea, they’re important for archives as a way to catalog the comics that have been made, particularly for comics with controversial material and by marginalized people.

While we have the internet now, the internet is a double-edged sword. On one hand, we still have laws that protect free speech and free posting on the internet (hello, Section 230). On the other, our opposition has made entire websites dedicated to harassment and stalking. However, there are plenty of places that explain how to deal with online harassment and help prevent it. We have the tools to make the internet a safe place to maintain the comics we love.

Support indie publishers and grant initiatives

Listen, we don’t have a lot of money in this industry. Actually, let me rephrase that: we do have a lot of money in the industry, it’s just not being spent and distributed properly (looking at you, HarperCollins). I’m an American, and I live in a country where making comics as a full-time job is prohibitive to many. This is why uplifting grant initiatives like the WeNeedDiverseBooks’ Walter Dean Myers’ Grant, Sloane Leong’s Minicomics grant, and Make More Comics’ micro-grant are important. Check out your local fellowships, or residencies. Donate to them if you can, and apply if you’re interested.

All in all, we have a lot of tools in our belt in order to be able get through these challenging times. We have history, help, the internet, and most importantly each other. We’ll get through this together.

E.B. Hutchins (she/they) is a writer and comic book artist in Massachusetts. She writes essays on the black queer experience and pop culture, and makes comics that center on queer women and people in a number of fantasy settings. When they’re not writing and drawing (or working at their day job), they’re crocheting or playing video games. You can find more of her work on Medium and on Twitter at @eb_hutchins.