Part One is available to read on the Cartoonist Cooperative Journal.

Shortly after the Comic Book Creators Guild fell apart in the eighties, a Creators Bill Of Rights was proposed by a number of the day’s movers and shakers, from Steve Bissette to Larry Marder. It was written in November 1988 for a two day summit of comic book artists. The meeting had been suggested by Cerebus creator, and noted creator rights advocate, Dave Sim, and it was hosted by Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird, creators of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The summit was a follow-up to a July meeting that had produced a “Creative Manifesto.” Some of the creators found the Manifesto a bit scattered, so Scott McCloud wrote a proposed replacement. “A Bill of Rights for Comics Creators” was accepted quickly on Sim’s suggestion, with only minor revisions.

Drawn group shot by McCloud, based on a photo, of the Summit participants

The following excerpt from the Creators Bill of Rights gives a snapshot of the group’s objectives:

For the survival and health of comics, we recognize that no single system of commerce and no single type of agreement between creator and publisher can or should be instituted. However, the rights and dignity of creators everywhere are equally vital. Our rights, as we perceive them to be and intend to preserve them, are:

The right to full ownership of what we fully create.

The right to full control over the creative execution of that which we fully own.

This manifesto clearly indicates the group didn’t intend on forming a union or even a group like a guild, but they wanted similar rights every guild or union in the industry has ever asked for. As Lanari would point out, though, just wishing and publishing those wishes would not be enough to secure these rights, indicating the need for a labor group.

And perhaps that is why, according to McCloud, “The Bill never generated much noise in the industry.” Unsurprisingly, The Comics Journal covered it at the time but few other outlets did. Despite this limited influence, it did dovetail with another movement that would become relevant shortly thereafter that would help lead to the formation of the first US union of comic workers. Crystallizing this important point, McCloud wrote:

A few years later, several top-selling Marvel artists would break from the pack and form a new company called Image, shifting the debate from rights and principles to clout and competition, but both developments would share a common premise, still relevant today: that comics creators already have the right to control their art if they want it; all they have to do is not sign it away.

One thing McCloud underemphasized, though, is that Image also focused on creator rights and ownership. It was a prime factor in Image’s formation, and it would prove to be a pivotal factor in an eventual Image union decades after Image’s founding.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Marvel comics illustrated by the seven artists who would go on to found Image (Jim Lee, Rob Liefeld, Todd McFarlane, Erik Larsen, Marc Silvestri, Jim Valentino, and Whilce Portacio) were selling enormously well. McFarlane’s Spider-Man #1 became the best-selling comic up to that point in time with 2.5 million copies sold. Shortly after that, Liefield released X-Force #1, briefly taking the record from McFarlane, and it sold 5 million copies. Hot on Liefeld’s heels, Lee’s X-Men #1 sold 8 million copies, a record that still has not been broken.

Image founders from left to right: Jim Valentino, Jim Lee, Erik Larsen, Rob Liefeld, Whilce Portacio, Todd McFarlane, Marc Silvestri

Despite fans flocking to comics featuring the talent of these creators, they still did not see any ownership over characters they created, and they did not see a cut of the merchandise that relied on their characters and art. They were compensated more than the average Marvel artist, true, but that slight advantage was tiny compared to the amount of money Marvel was making off their work. They also bristled at Marvel’s editorial control, leading to days filled with “silly mini-confrontations” according to McFarlane.

McFarlane, Liefeld, and Larsen were the first of the Image founders to talk together about forming their own company where they owned their characters and didn’t have to deal with corporate, editorial oversight. “I had been doing a lot of reading on the history of comics, and the one thing that became abundantly clear to me was that comic artists had been coming and going one at a time for decades,” McFarlane said. “It was easy to deal with one-in-one-out from a corporate perspective.” That perspective is something we’ve already seen in many places, especially the legal battle with Kirby, one that McFarlane also noticed. “I remember having this epiphany, saying, ‘Man, if they can do that to Jack Kirby — The King! — they can do that to anybody.’” With that context in mind, McFarlane, Liefeld, and Larsen decided that the best path forward for them, one that would remove them from the one-in-one-out corporate equation, would be to form their own company where every creator owned their own creations.

To stand out and be a success, they wanted more strength in numbers, so they began recruiting talent. Some creators expressed interest, like George Perez and Chris Claremont, but the eventual roster of Image founders became the seven artists already mentioned. Valentino was especially interested in forming Image, since Valentino had been deep in the independent comics movement before he came to Marvel. He summarized the founders’ shared philosophy: “We created the company that we wanted to work for, a company that would respect creators and their creations [by keeping the rights with creators]. We wanted to create the anti-Marvel, the anti-DC, because it was the right thing to do.” When Valentino would later become publisher of Image at the turn of the millennium, he would diversify the publisher’s lineup away from its initial focus on superheroes, making good on the promise to become the anti-Marvel and anti-DC. Espousing this philosophy, on February 1, 1992, the group sent out a press release announcing the formation of Image Comics.

At its formation, Image Comics didn’t have any formal structure for forming labor groups or negotiating with labor groups, perhaps reflecting a short-sighted or incomplete perspective by the founders. This perspective, though, owed much to the historical trend in comics of most creators fighting their own battles and reaping the spoils for themselves. But it was still a step forward, since it let creators retain ownership and profits from their work; Image Comics would take a flat fee to publish and distribute comics, but that was it.

Comics Buyer’s Guide #953 coverage of Image Comics founding and its initial, short-lived approach of publishing through Malibu.

Image Comics soon replaced DC as the second biggest comics publisher in the US. Marvel didn’t lose their top spot, but their sales did decline. While this didn’t last forever, especially once delays affected most early Image titles, it lasted for the first year or so of Image’s existence. Such strong numbers gave credence to the founders’ argument that they weren’t being properly compensated for the work they were doing, for the boost they had on sales.

That belief about compensation didn’t lead to creating or recognizing a formal labor organization to solve labor disputes until three decades later when a union was formed. And by that point the company would first treat the union the way Marvel and DC treated the Image founders. They would meet their demands with silence and inflexibility, at least at first.

Before the recent formation of a union at Image, there were a few other attempts at creating a labor organization for comics professionals, although these attempts were even shorter-lived and less influential than the ones we’ve already covered so a simple summary of these attempts will suffice.

In 2010, Tony Harris and Steve Niles tried to form the Sequential Arts and Entertainment Guild (SAEG). They posted on social media invitations to talk during Heroes Con about a guild that “will promote the professional betterment, health, and well-being of comic book pros. That’s it. Nothing else.” They didn’t want to go on strike or lead picket lines at publishers’ offices. Instead they wanted to use fundraising to help match money paid by creators toward group-rate health insurance and group-rate retirement plans, along with providing free tax advice. They also wanted to secure cover credit and royalties for colorists. Some creators joined, like Ron Marz, but SAEG shut down, if it could even be said to be open for business in the first place.

Two years later, in 2012, Eisner-award winning editor Rantz Hosely resumed the call for a comics guild. According to ICv2, “since the Guild would not be a union, it wouldn’t set rates, though Hoseley [saw] value in the organization defining ‘Guild Minimum Rates’ for projects executed on a Work-for-Hire basis.” Hoseley felt that the rates would have to be modified to reflect the finances of small, medium, and large publishers, and these rates would not be required of publishers. Instead Hoseley’s goal was to clearly define the rates and provide transparency in an industry that has long used secrecy to pay creators less. Like the other comic guilds before this, Hoseley’s didn’t get past the idea phase. Like the other comic labor organizations before this, it was long on ideals but short on unity, numbers, and commitment.

With all these failed attempts at creating a fairer workplace for comic creators and an organization that would fight for them, the situation for comic creators continued to worsen. Action was desperately needed, and the situation was approaching a boiling point.

For various reasons, the previous decade has seen comic creators (like other workers in the country) suffer blow after blow. And, just as workers in those other industries became fed up and started working with labor organizations to make meaningful changes, so would comic workers.

The first blow inflicted on comic creators centered around that ever-present topic, page rages. In 2023, The Comics Journal reported that they were told by a number of creators that page rates for rank-and-file freelancers had been falling across the board, especially in roles seen more as a supporting role, like colorists. An anonymous creator told them that “when [he] started working at DC a few years ago, the page rate was $121 a page,” but the page rate “at DC now for people breaking in is between $50 and $90.”

As in many industries in the US, some of the reason for this shift is due to publishers using less expensive, overseas labor. The same anonymous creator mentioned an important Marvel editor whose job was “to go overseas and start courting talent in Indonesia and India [and Brazil]…And it’s extremely exploitative to go there and universally drive down rates, because they’re incredibly talented creators, and they just happen to live in an area where it is less expensive than the U.S.” Worth noting, this creator added, is the importance “when we’re talking about this stuff to understand that these people who live in other countries…deserve fair wages, too.” For selfish and selfless reasons, the creator highlighted, creator and worker rights is a global issue that needs a global solution.

But this isn’t the only issue affecting page rates and leading to other financial shortfalls for comic workers. The thin profit margins of American comic publishers has led to cutbacks industry-wide and led to doubts among comic creators that a union or guild would be effective. Even worse, these creators worry that a union or guild could lead to short-term gains at the long-term cost of the industry. As the same creator told The Comics Journal:

I’ve talked to Dark Horse editors about what would happen if comics artists unionized and raised rates. And this editor said that, basically, Dark Horse would go out of business – like, budgets are so narrow that actual, affordable wages for most artists would put most companies out of business.

Most publishers and comic professionals felt they were stuck in limbo, a bad situation with no way out.

While this isn’t a unique feeling for comic professionals and publishers, since many of these worries were seen in the National/DC writers union formation, it certainly has gained more public attention in the age of social media. It’s also reached a tipping point in many professionals’ eyes, even if they couldn’t see a way out. In 2023, for instance, comics creator Ian McGinty died at the age of 38. His death was from natural causes, according to his family, but before that statement was made, McGinty’s death had already fanned a discussion on social media of overwork in comics. #ComicsBrokeMe was born.

That hashtag was used by thousands of people to share their heartrending experiences working in comics that echo ones we’ve seen throughout the history of the industry. In covering this event for Polygon, Rosie Knight highlighted the widespread nature of these experiences. Cartoonist Shivana Sookdeo told Knight that she knew the mistreatment of workers in the industry “just under the water like an iceberg,” but that it wouldn’t take much, like the #ComicsBrokeMe hashtag, to bring this harsh reality to light. Cartoonist Sloane Leone explained to Knight why this reality exists: “At the end of the day, we’re dealing with corporations who only care about maximizing profits. Human dignity isn’t a factor for them.”

Over the last decade, growing datasets have also been one of the ways these worries were made publicly available, providing quantitative evidence lacking in social media’s qualitative offerings. In 2013, for instance, Benjamin Woo released data on convention costs and earnings for comics creators, painting a dim light. In 2017, Stephanie Cooke released results of a pay rate survey.

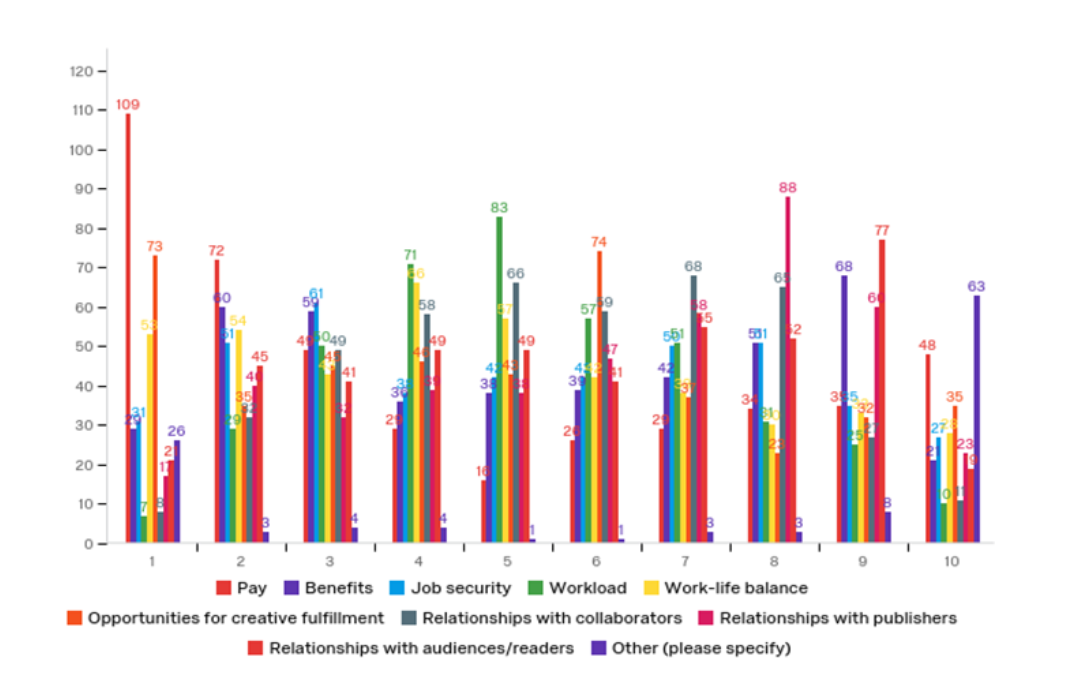

And in 2019, Sasha Bassett conducted 20-minute surveys with comic workers on financial realities, worker satisfaction, and workplace climate. Speaking to the Comics Beat, these were the results that concerned Bassett most:

Their overall work status was really interesting to me; 68% of participants were primarily freelance, working without an exclusive contract with a publisher. The stability of their income was shocking; less than 35% reported a stable income from their work in comics. That being said, it’s unclear from these data whether “stability” is due to consistently low (or no) income from said work. Rights and royalties were similarly shocking; while most participants owned *some* share of the rights to their work, over half had not earned any royalties for it. Most respondents reported experiencing health issues due to their work in comics. Work/life balance is a major issue; working in comics comes at the cost of restful sleep, time off for holidays or personal care, and involvement with their friends and families.

Bassett’s results reflected trends seen in other anecdotal evidence and data. The plight of the comic worker, like the plight of many other US workers, was dire. It was time for a change.

Graph of one of the results from Bassett’s survey that shows priorities for comic workers (1 being least important, 10 being most important)

Yes, there had been many times comic professionals wanted a change. Speaking to The Hollywood Reporter, former Marvel assistant editor Alejandro Arbona described how he and other staffers working at the House of Ideas repeatedly considered forming a union of their own. Arbona, though, said that more than anything else, general fear and uncertainty was what held them back. “I can’t even remember how many times my former Marvel co-workers and I floated the idea of unionization. For us, it was just idle speculation and wishful thinking,”Arbona said. “Unfortunately, we always came to the same self-defeating conclusions about who’d join us, who wouldn’t, and how the company would respond.” But now the situation was dire enough that this fear wouldn’t hold some comic professionals back.

As Shaun Richman said, “We are in a moment where there is real organizing heat amongst workers who have some creative bones in them, who have some critique of society as it exists, and how it should be.”. According to Richman, those workers “have generally reached the point of ‘fuck this shit. It’s time to fight back.’ And that is happening.” It’s happening in industries across the US, and it’s happening in the comic industry now.

At Image Comics, this gloomy treatment of comics workers led to a historic fight in that it was the first to succeed at forming and ratifying a union: the Comic Book Workers United (CBWU). To get around the work-for-hire/freelance dilemma, the CBWA would only consist of full-time workers that handled more of the publishing side of comics: marketing, payroll, editing, and similar jobs.

Gita Jackson, writing for Vice, described what made the Image workers form CBWU, a list of grievances we’ve seen before with the added wrinkle of COVID:

Before workers handling editing, marketing, and payroll at the company formed a union, conversations about doing so had been in the ether for a long time. And after four employees in an already small office were fired during the pandemic and their roles not replaced, it showed the workers at Image how necessary a union was, and how universal the struggle for better working conditions really is.

In a statement on the CBWU website, the group summarizes what led to their founding: “For years, comics publishing workers have watched our professional efforts support creators and delight readers. Sadly, we have also watched that same labor be taken for granted at best and exploited at worst.”

CBWU–when talking to Vice as a collective, the way they handle all press contact– made sure to point out that “this situation is not unique to Image. It’s not even unique to comics.” As in comics and other industries, when roles are not replaced, that just means more work–without more pay–for the existing employees, increasing pressure on an already over-worked and vital part of Image’s publishing process.

Still, it is important to outline the problems at Image that made CBWU members take action. David Brothers, an editor for comics publisher Viz and former Image Comics employee from 2013-2017, told Vice that many of the issues at Image had been brought up before CBWU was formed, but that they weren’t resolved because the company hasn’t evolved as it moved from a small indie to a bigger independent publisher. “I always described it as a big business that used to be a small business that never made the step up,” he said. “Image is independent but not indie.”

This stagnation has led to outsized expectations for all their staff, especially their publishing staff that would form CBWU. “When I first started production,” Brothers recalled, “working until after dark on a Friday to get books to print was, you know, normal.” (“This has not been the case since 2019 when the printers’ deadlines were adjusted on the production schedule so that they no longer land on Friday,” an Image spokesperson said. “Now they land on Tuesday with room for Production to address late files during weekday work hours.”)

Other Image staffers and the CBWU press releases have confirmed that changes like the one mentioned by the Image spokesperson were largely cosmetic and hadn’t done much to reduce workload, improve pay and benefits, or lead to better treatment overall. Facing these pressures with little to no support from management, the Image workers knew they needed a change. But since these workers weren’t the creatives associated in the public eye with comics, like writers or artists, they were passed a double edged sword. They weren’t well-known enough to use public pressure to achieve individual change like Siegel, Shuster, and Kirby did; but they did have full-time status, leading to their ability to form a union without any legal gray areas.

Although comic creators knew the work these future CBWU professionals put in, most of the general public didn’t. The work these people did to get comic books in readers hands are largely invisible to readers but vital to creators and a reader’s experience. “We help to make sure creators are paid on time. We assist in the marketing for the books. We work directly with distributors and retailers to put these books on the shelves.” In short, the CBWU says that they “work behind the scenes to give our creators the best possible success on their creator-owned stories” that can’t be replicated by the creators themselves.

When CBWU first started gaining exposure in its fight for the union to be recognized and ratified, many comic creators offered their support. Even if they couldn’t join the union, they wanted these professionals to know that a union was a valid path for such important, overworked roles. Writer Dave Scheidt said that he knows these professionals are there for him and other creators: “Somebody is organizing a print schedule, somebody’s sending it to the printer, there’s all these million things I never could do. I [and other creators] would have no idea how to do any of that stuff.” Scheidt elaborated on why the formation of a union and the publicity associated with it would be beneficial. “I think that’ll help the industry in general, just being conscious of the amount of work that people put into all this behind the scenes stuff,” Scheidt said. “It’s very thankless work, nobody really shouts them out.”

Longtime comic creator Dan Jurgens, who worked on The Death of Superman, said that although the writers and artists might get the most credit, every other person who works on a book serves a vital function towards getting it to the reader, especially an editor. “Your job as an editor, in some ways, is to manage the workload of all the freelancers who are working for you,” he told Vice. “Let’s say you’re editing four titles. You might have four issues of each of those titles in various stages of production on any given day. Some of them at the end of the chain are heading right for the printer, and you’re trying to get it out. Managing that in this age of email, and changes and everything else that occurs, it’s really a remarkable amount of work.”

Scheidt and Jurgens both said that Image was the perfect place for change within the industry because of how it was founded. In their own press releases, CBWU echoed this sentiment. “As with many great union stories,” CBWU said, “the founding of Image Comics started with a group of people who knew the value of their work and had strong convictions about what they deserved to get out of the industry they loved and helped make possible.” Ultimately, Image was founded, CBWU argues with the understanding “that individual workers have a right to benefit from their labor and that self-determination should be available to everyone, not just a powerful few. That philosophy is something we are carrying forward with this union.”

Jurgens offered his own take on what this philosophy and the changes it demands could look like, saying that “the biggest thing I would want would be a reasonable workload.” Not only would it improve that professional’s work-life balance, it would improve the products themselves, Jurgens argued. “That would allow me to manage my books and projects to their best possible conclusion. It seems like common sense, but it can be hard to find because some systems are so overloaded.”

In one of their statements, the CBWU summarized the above points that led them to organize. “The uncertainty and lack of control in our workplace has persisted,” said CBWU. They also wrote that their formation and the public support,“along with an overall wave of labor organizing, and civic action in general” helped them find the resolve to stick with forming a union. “[P]eople everywhere are advocating for themselves, and it’s as good a time as any for us to do so as well. We love our jobs and the work we do, but we also know that we deserve to be fairly represented. Everyone does.”

CBWU offered more specifics about the labor inspirations outside the comics industry.

They were inspired recently by IATSE, a union of crew workers in the entertainment industry, the AWU, the union of Google workers, and organizers working in warehouse fulfillment centers. Closer to the geek culture that comics call home, they were inspired by workers at the tabletop role playing game publisher Paizo, who organized with the Communications Workers of America, a labor giant organizing workers across multiple industries.

With these influential groups inspiring them, and with their own frustration at a high point, on November 1, 2021, 10 of 12 eligible staffers voted to organize and go public, forming the CBWU and initiating the process of making it a recognized union. Like Paizo, CBWU was assisted in this process by the Communications Workers of America. “Labor organizing is something the staff at Image Comics have been discussing for a few years,” the Image staffers told The Hollywood Reporter at the time. “Many of us have backgrounds in or adjacent to unions, including several of the founders, whose work being successfully adapted for the big and small screen has meant working with or, in some cases, actually being represented by unions.”

Despite the founders’ experience, CBWUs November 5 deadline passed with no official response from Image as a company. For the time being, Arbona and other professionals’ fears of a negative response from employers seemed well-founded. The company did issue a statement earlier that day, though, that the National Labor Relations Board was reviewing the petition filed by the CWA to allow eligible members of Image’s staff to vote for CWA representation. The statement ended with generic, corporate-PR language, “Everyone at Image is committed to working through this process, and we are confident that the resolution to these efforts will have positive long-term benefits.”

What demands led to this relative silence? In their opening salvo, CBWU outlined nine goals, which included demands like greater transparency of staff salaries and workloads, the addition of more staff and a more diverse pool of staffers, and the continuation of remote work options. Missing among those demands was any explicit call for higher wages. “Because Image management was unwilling to negotiate with us on anything outside of wages, benefits, and working conditions as they have traditionally been defined,” CBWU said, “we were not able to include most of those items in our contract.”

This was a strategic decision that the union believed was misinterpreted by Image management as showing little concern over current pay, despite their request for increased compensation when an employee’s work dramatically increased. It is true, though, that the CBWU had different priorities:

From the beginning, our priority was to encourage the hiring of more staff to address untenable workloads and hopefully make a better work-life balance more achievable. To our dismay, Image management disingenuously interpreted this as the union requesting to be switched to an hourly pay rate and to be made eligible for overtime pay. We were all salaried workers and did not want to lose the security and flexibility that came with that, but the compromise we achieved was a structured annual wage increase schedule that we’re all happy with.

Yet more controversy sparked over what some call the “veto clause” and what CBWU described as “a collective voting option to immediately cancel publication of any title whose creator(s) have been found to have engaged in abuse, sexual assault, racism and xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, ableism, etc.” For a union formed to amplify their voices, this seems hypocritical and antithetical to Image’s philosophy, something Image and others picked up on right away.

Shortly after the goals were published, an Image company spokesperson broke their silence to tell Vice that “Image was formed because the founders wanted to build a company where they and other creators could own and control their work without interference from their publisher.” The Comics Journal did report, though, that “[i]n the same article, CBWU countered that the demand was one designed to protect employees from what they considered unsafe or uncomfortable environments owing to the content of their work they published, or the behavior of the creators behind it.” In short, they wanted to silence hateful voices to feel comfortable using their own.

Further justifying this position, CBWU told The Comics Journal that “our list of goals was aspirational, including the controversial ‘veto clause.’” Such a clause arose because “Image Comics has made it clear that they have no desire to listen to the concerns of their employees when it comes to decisions of who or what to publish.” And it’s worth noting that this is just a goal, and that CBWU, “as with [their] other goals…hope[s] to revisit…during the contract renewal phase.”

These rationales left many dissatisfied, leading many to interpret this as a demand for a censorious panel to ensure that upcoming comics adhere to political correctness. In their article, though, Vice admitted that “It is perhaps more properly read as a response to past incidents including the Chaykin cover and the disastrous Warren Ellis situation, in which the company was caught in a bind after the well-respected writer was called out for predatory behavior.” Instead, Vice suggests, this is more a demand to have “on the table for negotiation a defined process for dealing with creators doing or saying objectionable things—a process that might, if laid out properly, do as much to protect creators who find themselves in the middle of [controversy.]”

“This is in no way an effort to dictate the content that creators publish. This is a question of our right to a safe and comfortable working environment,” CBWU elaborated later on. “There is no way to know what this process would look like at this time, given that this list of goals is just that, and union negotiations and collective bargaining exist for a reason. This is simply a statement of intent to reclaim power over situations in which we feel helpless, which is pretty much what unionizing is all about.”

“What they’re saying is that it’s not about the content of the comics, right? It’s about what the creators have done,” Brothers explained. “It’s about abuse, essentially. I think people are reading it as they want oversight on what goes into the books. Really, it’s like, ‘We don’t want to work with creeps.’”

Despite this clause’s controversy, or maybe even because of the protection implied by it, CBWU moved forward. Still meeting silence from Image, with Image declining to recognize the union voluntarily, CBWU voted 7-2, under the supervision of the National Labor Relations Board, in January 2022 to become a union. With this vote, Image Comics became the first unionized comic book publisher in the US.

“We love our jobs and we love comics. We believe that unionization will make us better able to do our jobs well, and more sustainably, in the long run,” CBWU said at the time. “Winning this election is only the beginning — as always, we are #drawninsolidarity and are eager to continue working together with CWA on the next steps towards securing a strong, fair, and exemplary first contract for comic book publishing workers.” And they also wanted other comic professionals to take these steps: “We want to stress how crucial it is for all workers to know they are worthy of respect, fair treatment, fair compensation, and recognition for their time and effort. The NLRB, NLRBGC, and the CWA have been a boon of resources on how to get started on the path to unionization.” They concluded that it is their “sincere hope that today’s win inspires our peers to organize for a democratic voice.”

Still figuring out next steps of their own, Image and its prominent employees were still largely silent. Robert Kirkman, co-creator of The Walking Dead, declined comment, as did the Image founders. But growing public pressure and a pivotal development at another US comics publisher would soon change their minds.

Fueled by the success of the CBWU and the pain of their own frustrations, staff at US-based manga publisher Seven Seas Entertainment announced their own union

in May of 2022. Unlike Image Comics, Seven Seas Entertainment recognized this union voluntarily sooner in the process, although, like Image, they too resisted it at first.

Like CBWU, these workers were full-time employees in editorial, prepress, design, administration, and other roles. However, according to the collective statement released by these workers, “full-time employees of Seven Seas Entertainment receive no benefits or protections. The only difference between a permalancer and an employee at the company is how their wages are processed by accounting. A permalancer is responsible for filing self-employment taxes, for example.” They wanted more benefits and rewards, given their full-time status, work climate and responsibilities.

In announcing their union, Seven Seas staff echoed similar sentiments as CBWU workers and other comics professionals. True, Seven Seas focused on manga and webtoons and their growth took a different trajectory, but the Seven Seas workers echoed past professionals’ plights in their statement: “With rapid growth comes growing pains, and we, the workers of Seven Seas, have been shouldering much of that pain. We find ourselves overworked, underpaid, and inadequately supported.” Possibly even worse, they said, “we do not receive the vacation, sick days, family leave, health insurance, and retirement benefits otherwise typical of the publishing industry…Like workers in every sector of the entertainment industry, we are burnt out, and unfulfilled promises of ‘imminent’ benefits have worn thin.”

The Seven Seas staff organized for about five months, reaching out to the CWA for support in the process much as CBWU had done, to form the United Workers of Seven Seas (UW7S). Representatives from UW7S told Publishers Weekly that CWA connected them with a representative to walk them through the process of organizing.” This involved careful planning, numerous meetings with our CWA rep, and a lot of spreadsheets! We arranged private chat spaces, hired artist Revel Guts to design our logo, and built our website during that time.”

After all this work, they had a supermajority of supporters who had signed union cards, so they announced their union to Seven Seas Entertainment management on May 23, 2022 for recognition, while simultaneously publicizing the UW7S formation and request for recognition on social media. With the formation of the UW7S union, they released a list of 16 goals to improve working conditions in response to documented workplace grievances. These goals included healthcare, paid leave, pension benefits, and paid time off and vacations, reasonable workloads, protections and benefits for freelancers such as kill fees and revision fees, and anti-harassment policies and grievance procedures.

The UW7S statement concluded: “We’re eager to produce the best products we can, and the best way to do that is with a living wage, proper hardware and software, and a well-organized digital office. As a union, we seek to negotiate better working conditions for both Seven Seas employees and the many freelancers who make what we do possible.” This last point, about creating better conditions for freelancers, isn’t elaborated on, but it most likely means that creating better treatment for full-time workers will create a baseline that will then apply to freelancers also, even if they were not represented by the union and the union’s collective bargaining.

At first, Seven Seas management didn’t voluntarily recognize UW7S, releasing the following statement: “We respect the rights of our employees to choose or not choose union representation.” Still, despite that respect, they stood firm in not recognizing the union at that point. “While we have been requested by a number of employees to voluntarily recognize the [Communications Workers of America] as their legal representative—without [a National Labor Relations Board] conducted election—we have decided to respect the right of all eligible employees to vote on this issue.” Not only did they refuse to recognize the union at the time, UW7S claimed on Twitter that Seven Seas was using the time before a possible National Labor Relations Board election to hire “union-busting” firm Ogletree Deakins, a firm that Business Insider said was accused of holding “fear mongering” anti-unionization PowerPoints amid IKEA worker unionization efforts back in 2015.

Despite Seven Seas’s refusal to voluntarily recognize the union and the hiring of Ogletree Deakins, UW7S maintained at the time that they were confident they would win recognition in the end, even if Seven Seas forced the issue into an NLRB election. “We already have 32 of 41 eligible members with signed union cards,” UW7S said in a public statement, “and we firmly believe that unionizing is the best way to ensure equitable treatment of all staff and freelancers, as well as the continued success of the company as our industry continues to boom.”

UW7S’s confidence wasn’t misplaced. A little over a month after the union contacted Seven Seas management, Seven Seas Entertainment reversed their earlier decision and, without holding a National Labor Relations Board election, recognized UW7S as the union representative for its workers.. In an official statement on June 25, 2022, UW7S announced the news that “Seven Seas has agreed to voluntarily recognize us as the union based on a majority card check.” The statement continued by noting that this agreement “will pave the way for a more expedited path to bargaining a first contract.” They had become the first unionized manga publisher in North America.

For once, it seems, a corporation did the right thing for its workers without much prodding or public pressure. In recognition of this, after the initial adversarial language, UW7S added some admiration for Seven Seas, writing that “at a time when many employers continue to fight the unionization of their employees, we appreciate that Seven Seas decided to respect the voices of the majority of staff and recognize us. We look forward to developing a mutually beneficial relationship and reaching a collective bargaining agreement in the near future.” UW7S added that “the public support and enthusiasm for our campaign on social media has been heartening!”

CBWU had been one of the sparks for UW7S’s formation: even though CBWU had been fanning their own flames for longer, UW7S started their own fire sooner due to Seven Seas being more responsive and cooperative than Image Comics. But CBWU wasn’t too far behind.

Nearly a year after their union election in January 2022, CBWU would finally ratify their first contract on March 1, 2023. While Image Comics had been resistant to work with the group, CBWU did clarify for The Comics Journal that “Image management had a legal obligation to recognize our union when we won our election in January of 2022.” The company’s silence was merely an act of biding time until the inevitable.

Following union recognition came the long process of collective bargaining. Then, on March 1, CBWU and Image Comics ratified their first union contract–one that will last three years and then lead into another round of collective bargaining. With the contract’s ratification, CBWU became the first recognized union among mainstream comic publishers in the US. For The Comics Journal, Zach Rabiroff wrote about the historic nature of this moment. He admitted that even though “the CBWU’s membership is small, and their position still unique in the industry”, this was still good news, because “the March contract ratification is nevertheless a watershed in the story of the comic industry’s collective action: the first time that a concerted effort on the part of one publisher’s employees has resulted in legally-recognized and potentially significant gain.”

The next day, on March 2, CBWU released a statement about the ratification, focusing on gratitude for the support they, like UW7S, received from the public:

We were hopeful for, but could never have imagined, the outpouring of support we received when we began our collective bargaining journey. A lot has happened since that first announcement and we cannot begin to adequately express our gratitude to the community of people within and without the industry who have stood with us during contract negotiations.

CBWU then moved onto placing this ratification in the context of a larger journey for them and for the comics industry at large:

Now that we have an agreed-upon contract, the next step will be to make sure everyone is familiar with the terms of the contract and to put it into action. We started at Point A and have mutually agreed upon a Point B, but some of the finer details may necessitate further discussion with Image. We anticipate some growing pains as both the workers and managers acclimate to the numerous changes that are being made. The big picture is to look at what we were able to accomplish this round, and come up with ways to build upon this framework for our next contract negotiation…As we celebrate this victory, we also want to take the opportunity to reaffirm that this contract is just the first step among many and we hope you will stick with us as we continue the fight for union representation and more equitable working conditions for everyone in the comic book industry and beyond. In closing, to those of you out there agitating, advocating, and organizing, we see you and we can’t wait to see, “What’s next?”

Despite Image working with CBWU on this ratified contract, it may come as no surprise that they remained largely silent following the announcement of the contract. Rabiroff received no reply from Image for his Comics Journal piece. CBWU has expressed dissatisfaction with their company’s silence, along with their resistance during this process.

We have yet to be contacted by Image management since we held our ratification vote. There’s been no formal response, and the progress we’ve made so far has been hard-won by our bargaining committee. The temperature of the water has been lukewarm at best – we’ve encountered significant resistance throughout the entire process. We expect all managers to be educated about the terms of the contract, and we will hold them accountable if they violate those terms…. It has been frustrating. There’s been only obligatory participation in the process on the part of the company with very little willingness to discuss terms during bargaining and most proposals being met with cursory rejection…The contract lays a foundation. We now have a formal procedure to address issues as they arise and structured annual wages which address our goal of more transparency. Workers who form unions often face the kind of resistance we saw from Image Comics. It’s an attempt to demoralize us and break our unity. Sometimes the stalling tactics succeed, and workers never win first contracts.

Even though CBWU notched a win for workers’ rights, it still seems there will be many battles to fight.

But they encourage those who want to fight these battles. “It’s absolutely possible for workers anywhere to join together and form a union, and we highly recommend it to every single worker,” CBWU said. “One of the challenges at larger companies like Marvel or DC is that they would likely have even more resources at their disposal to hire union-busting attorneys to intimidate their employees.” Don’t be discouraged, though, CBWU said. “We’ve seen workers take on some of the largest corporations in the world and win. This wave of organizing isn’t ending anytime soon.”

In fact, this November, workers at Canada-based publisher Drawn & Quarterly unionized, becoming the third comic publisher in North America with a union. They formed their union under Canada’s second largest trade union, the Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN), with the union certified by the Administrative Labor Tribunal of Quebec. Employees for both the publishing and bookstore arms of Drawn & Quarterly are covered, joining the tide of workers organizing for better transparency, salary, and working conditions.

Scheidt and Brothers, when speaking of CBWU’s success, explained how one of these changing tides might have led to CBWU’s victory. Both said that none of this would be possible without Gawker (a digital media company) organizing with the Writer’s Guild of America East in 2015. Just like labor organization within one comic publisher can aid organization in another publisher–like CBWU helped pave the way for UW7S’s own win–labor movements in one industry can aid movements in others.

Both within the comics industry and beyond, hope persists that stories like CBWU’s will help inspire action by other professionals needing better treatment. Before contract ratification, Brothers said that “I think if it works at Image, it would definitely lead to a wave of other publishers unionizing.” He noted that Dark Horse and Oni are based in the same city as Image: Portland. Scheidt echoed similar sentiments: “I think it’s opening this conversation up and it’s not this…hush hush thing, like we’re not supposed to talk about it.”

Workers’ rights can now be spoken about with a full voice in a battle that can be won. And Bassett gave this advice for the future fight: “Folks also seem overwhelmed with the scale of unionizing comics. To this, I say that it is not an individual’s job to do all of the work…Talking to your peers, sending a few emails, showing up to meetings, all of these small efforts add up – ‘showing up’ is often the most powerful thing you can do to support the effort of folks who are organizing.” This support won’t go unrecognized.

“We wish we could share the sheer volume of responses we have received from people working at other publishers, asking for advice on how to start the process themselves,” CBWU said after the contract’s ratification. “As it stands, all we can do is put them in contact with the fantastic people at the CWA, wish them well as they begin their own journey, and promise to stand up for them when they decide to go public, as they have stood up for us.”

“Management in every industry in the United States has been hostile to union organizing — the comic book industry is no different,” a CWA rep said in a different public statement. “What is different is that workers are fed up and ready to use the power they have when they join together to make real changes. When workers are ready to organize, we are ready to help them.”

“We hope this is just the beginning of a tidal wave of unionization in this country,” CBWU concluded. “It’s long overdue.”

CJ Standal has taught and written about comics for years (chronicled and collected in Outside the Panels: Comics, the Classroom, and the Creative Life); he also has written comics of his own, including Rebirth of the Gangster, published by CJSP, and B.A.E. Wulf, published by Markosia. He is currently finishing his first fictional prose novel, Mapping Mythland.

Bibliography

Adolphus, Emell Derra. “Image Comics Union Ratifies First Contract.” PublishersWeekly,

PWxyz, LLC, 3 Mar. 2023, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/

comics//article/91682-image-comics-union-ratifies-first-contract.html.

Asselin, Janelle. “1978 Creators Guild Wanted Rates That People Still Don’t Get.”

ComicsAlliance, Townsquare Media, Inc., 11 May 2015, www.comicsalliance.com/

Ayres, Andrea. “Will Comics Ever Get a Union? Sasha Bassett Plans to Find Out.” The Beat,

Superlime Media LLC, 10 Mar. 2020, www.comicsbeat.com/sasha-bassett-comics- union/.

Carlson, Johanna Draper. “Drawn & Quarterly Workers Unionize.” ICv2, 17 Nov. 2023,

www.icv2.com/articles/news/view/55629/drawn-quarterly-workers-unionize.

Colbert, Isaiah. “First Manga Worker Union Forms Amid Alleged Union Busting.” Kotaku, 31

May 2022, www.kotaku.com/seven-seas-entertainment-manga-union-united-workers-in-

Cooke, Jon B. “A Spirited Relationship.” Will Eisner Interview – Comic Book Artist #4 , Two

Morrows Publishing, www.twomorrows.com/comicbookartist/ articles/04eisner.html.

Cronin, Brian. “How Neal Adams Fought for the Most Important Superman Byline Ever.” CBR,

Comic Book Resources, 6 May 2022, www.cbr.com/neal-adams-superman-fight-siegel- shuster-byline-credit/.

Dean, Michael. “Kirby and Goliath: The Fight for Jack Kirby’s Marvel Artwork.” The Comics

Journal, Fantagraphics, 1 Oct. 2021, www.tcj.com/kirby-and-goliath-the-fight-for- jack-kirbys-marvel-artwork/.

Doherty, Brennan. “Why the US Embraced ‘Strike Culture.’” BBC News, BBC, 28 Sept.

2023, www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20230927-how-strike-culture-took-hold-in-the-us- in-2023.

Elbein, Asher. “Marvel, Jack Kirby, and the Comic-Book Artist’s Plight.” The Atlantic, The

Atlantic Monthly Group, 1 Sept. 2016, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive

/2016/09/marvel-jack-kirby-and-the-plight-of-the-comic-book-artist/498299/.

“Freelancers Union: Mission.” Freelancers Union, 25 July 2023, www.freelancersunion.org/

Gatevackes, William. “Comic Creator Credit: Why Not Unionize?” FilmBuffOnline, 22 Oct.

2021, www.filmbuffonline.com/FBOLNewsreel/wordpress/2021/09/10/comic-creator-

George, Joe. “Neal Adams and the Fight to Unionize Comics.” Progressive.Org, 5 May 2022,

www.progressive.org/latest/neal-adams-fight-to-unionize-comics-george-220505/.

“A Guild for Comic Book Creators?” ICv2, 17 Dec. 2012, www.icv2.com/articles/comics/view/

24624/a-guild-comic-book-creators.

Harper, David. “The House of ‘The Walking Dead.’” The Ringer, Spotify AB, 1 Feb. 2017,

www.theringer.com/2017/2/1/16041010/image-comics-25-year-anniversary-the-walking-dead-e4774b7bffcd.

Jackson, Gita. “The Image Union Is the Future of Comics.” Vice, Vice Media Group, 22 Nov.

2021, www.vice.com/en/article/y3vdbx/the-image-union-is-the-future-of-comics.

Johnson, Destiny. “Image Comics Will Not Voluntarily Recognize Union.” KGW8, KGW-TV, 14

Nov. 2021, www.kgw.com/article/entertainment/nerd-news/image-comics-union/283-632

71a11-5e86-4c72-ae40-59e5d5b0f24f.

Johnston, Rich. “Comic Book Workers United Is Now America’s First Comic Book Union.”

Bleeding Cool News And Rumors, 7 Jan. 2022, www.bleedingcool.com/comics/comic-

book-workers-united-is-now-americas-first-comic-book-union/.

Johnston, Rich. “Comics Creators – Together We Will Stand?” Bleeding Cool News And

Rumors, 7 May 2010, www.bleedingcool.com/comics/recent-updates/comics-creators-

Johnston, Rich. “So Why Are There No Comic Book Unions Then?” Bleeding Cool News And

Rumors, Bleeding Cool News, 21 Oct. 2018, www.bleedingcool.com/comics/comic-book -unions/.

Kennedy, Hank. “It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane…nNo, It’s a Union!” Tempest, Tempest Magazine, 9

Mar. 2022, www.tempestmag.org/2022/03/its-a-bird-its-a-planeno-its-a-union/.

Knight, Rosie. “The Comics Industry Has Left Creators to Drown, So Some Are Building

Lifeboats.” Polygon, Vox Media, 13 Oct. 2023, www.polygon.com/23914388/comics- broke-me-page-rates-creator-union-cartoonist-cooperative-hero-initiative.

Kleefeld, Sean. “The Creator’s Bill of Rights.” Kleefeld on Comics, 20 May 2021,

www.kleefeldoncomics.com/2021/05/the-creators-bill-of-rights.html.

Lanari, Austin. “Unionize Comics: The Comics Guild and the Possibility of Collective Action.”

The Comics Journal, winter 2018, pp. 120–137.

“Labor Unions.” National Museum of American History, 2023, https://americanhistory.si.edu/

american-enterprise-exhibition/consumer-era/labor-unions.

Lauer, Jonathon. “The History of Image Comics.” The Nerdd, 27 Aug. 2020, www.thenerdd

.com/2018/11/30/the-history-of-image-comics/.

McCloud, Scott. “The Creator’s Bill of Rights.” ScottMcCloud.com, www.scottmccloud.com/4-

McMillan, Graeme. “The Comic Book Industry’s Next Page-Turner: Union Organizing.” The

Hollywood Reporter, 22 Nov. 2021. www.hollywoodreporter.com/business/business-

news/the-comic-book-industrys-next-page-turner-union-organizing-1235044157/.

McMillan, Graeme. “Image Comics’ Workers Union: Everything You Need to Know About

Comic Book Workers United.” Popverse, 22 Sept. 2023, www.thepopverse.com/image

-comics-union-comic-book-workers-united-update.

McQuarrie, Fiona. “Unionizing Comics.” All About Work, 28 June 2019, www.allaboutwork.org

/2019/06/27/unionizing-comics/.

Paul, Ari. “A Union of One.” Jacobin, 2023, www.jacobin.com/2014/10/freelancers-union/.

Pofeldt, Elaine. “A New Safety Net for Freelancers.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 25 June 2014,

www.forbes.com/sites/elainepofeldt/2014/06/25/a-new-safety-net-for-freelancers/?sh=24

Pulliam-Moore, Charles. “Ex-Marvel Editor: ‘Self-Defeating Conclusions’ Prevented

Unionizing.” Gizmodo, 23 Nov. 2021, www.gizmodo.com/ex-marvel-editor-alejandro-

arbona-says-self-defeating-1848112042.

Rabiroff, Zach. “At Image, Comic Book Workers United Takes Another Step in a Long Union

Walk.” The Comics Journal, Fantagraphics, 12 Mar. 2023, www.tcj.com/at- image-comic-book-workers-united-takes-another-step-in-a-long-union-walk/.

Reed, Patrick A. “Today in Comics History: The Start of the Image Revolution.”

ComicsAlliance, Townsquare Media, Inc., 1 Feb. 2016, comicsalliance.com/

Reid, Calvin. “Seven Seas Staff Launches Effort to Form Union.” PublishersWeekly, PWxyz,

LLC., 24 May 2022, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/comics/

article/89415-seven-seas-staff-launches-effort-to-form-union.html.

Reid, Calvin. “Seven Seas Voluntarily Recognizes Union.” PublishersWeekly, PWxyz, LLC, 28

Shooter, Jim. “The Jack Kirby Artwork Return Controversy.” JimShooter.com, 1 Apr. 2011,

www.jimshooter.com/2011/04/jack-kirby-artwork-return-controversy.html/.

Thomas, Ian. “A Brief Interview with United Workers of Seven Seas.” The Comics Journal,

Fantagraphics, 9 June 2022, www.tcj.com/a-brief-interview-with-united-workers-of-

Westcott, Kevin. “2023 Digital Media Trends Survey.” Deloitte Insights, 14 Apr. 2023,