There’s always been something in the air, but lately it’s spread to our veins and voices.

This past season has been called the summer of strikes. Hollywood writers put down their pens and picked up picket signs. Auto workers walked off the lines to a bargaining table. Pilots were on the ground instead of in the air, nurses jotted down demands instead of vitals, and hotel staff refused to clean up rooms unless their contracts were cleaned up.

Last year, there were 20 major labor strikes in the United States, an increase of 25% over the average for the prior two decades. 2023 looks on pace to match or beat that statistic.

Even industries that narrowly averted strikes, like shipping and transportation, have felt the hot breath of worker demands traveling down their necks. That might be because a recent Gallup poll puts labor union approval at a 15-year high.

Worth noting is that unions are growing particularly fast in media and publishing, where economic conditions have resulted in unprecedented change. Rising inflation hasn’t been matched by raises. Work demands have increased without a similar increase in compensation. AI threatens many jobs involving baseline writing. Many of these trends stem from the larger trend of companies cutting positions and shifting that work onto other employees who are already feeling overworked. These changes are partly because–while media consumption of TV, movies, video games, and social media has increased–the numbers for other digital writing and publication have largely stagnated. Due to these and other reasons, there has been more demand for unions, both in industries across the US and in the digital marketplace. In fact, the number of unionized workers in internet publishing has increased a whopping 20-fold since 2010.

And this year, without initiating a strike, the first comics union in the US (Comic Book Workers United) had their first contract ratified.

It’s been a long road to get to this point. Workers in the comics industry have seen many false starts before finally gaining some traction, whether those efforts came from a union, a guild, or some other type of organized labor. Yet the victory of today’s comic creators owes plenty to the losses of those who came before and to the second winds that helped them push to their own finish line.

Of course, there are plenty of other races to run. We need only look at #ComicsBrokeMe to see a litany of stories documenting the conditions comic workers fight against and what happens when they lose that fight. But, before peering ahead, we must take a look in our rear view mirror at both the successful Comic Book Workers United and the efforts that didn’t end with comic creators breaking through the tape at the finish line.

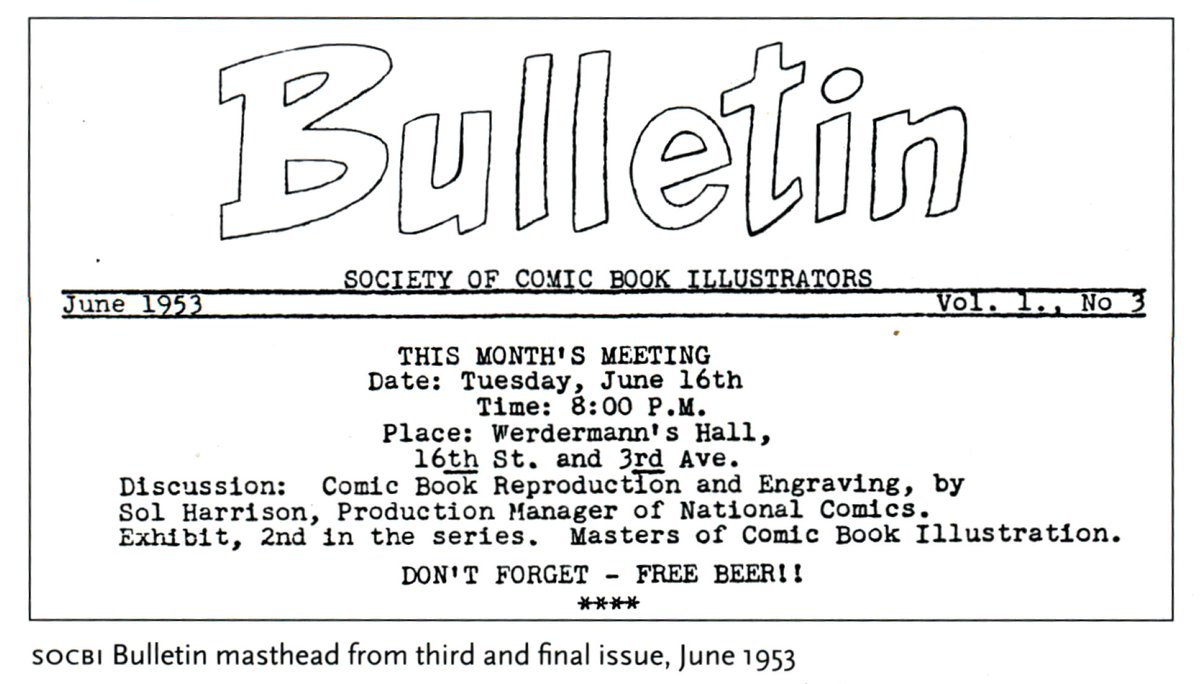

The first documented attempt at creating a union in the American comics industry was in 1951. That year, EC Comics artist Bernard Krigstein created the Society of Comic Book Illustrators. Krigstein’s intentions in organizing workers did not extend to the creation of a union for illustrators and writers (not to mention other creatives, like letterers); such solidarity and numbers might have helped their cause. Whatever the reasons the union was exclusive to illustrators, later attempts at forming a union often duplicate this error.

Originally called the Society of Comic Book Artists, Krigstein changed the name to appear more “prestigious”, according to Tempest Magazine’s Hank Kennedy, because Krigstein “believed comic books were a serious art form, on par with literature and music”. And he thought that such a serious art form demanded serious guidelines for worker treatment.

Just what were Krigstein’s serious guidelines? Krigstein and the Society of Comic Book Illustrators demanded the return of original art to the artist as a standard in work contracts, the establishment of a minimum page rate for all artists in the industry, and the creation of a fund paid by the publishers that would provide comprehensive medical coverage. Such demands would occur again and again from most unions and guilds in the comic industry over the years. Dues to join the fight and the Society of Comic Book Illustrators were five dollars a month. It’s unclear how many creators would have been working as full-time employees under contract with their publisher and how many were work-for-hire, which is a pivotal distinction in forming a union and one we’ll explore more later. At the first meeting, however, there was enough momentum for Krigstein to be unanimously elected president of the union.

However, that unanimous approval would be a rare phenomenon in the Society of Comic Book Illustrators. According to Kennedy, “From the beginning there was a split in the membership as to what the purpose of the organization would be. The older, more established artists wanted the organization to exist as a professional organization, with a more congenial relationship with the publishers. The younger artists wanted the organization to be a labor union that would be more combative.” This division empowered publishers to weaken and ultimately cause the dissolution of the Society of Comic Book Illustrators.

In March 1953, National Periodical Publications (which became DC Comics) was the first publisher to launch a salvo at the union. Through their representative Robert Kanigher, they attacked the artists for the audacity of calling themselves illustrators, and made veiled threats regarding the continued employment of Society members. Other publishers joined in intimidating and wooing artists away from the union. Artist Gil Kane reported that prominent Society members were bought off by the main publishers in exchange for job security and higher page rates. This divide and conquer tactic was used frequently in fighting unions, guilds, and other labor organizations.

In the case of the Society of Comic Book Illustrators, these tactics proved effective. Over the next few months, membership in the union declined, and it held its last meeting in June of the year it was founded, 1953. Krigstein had stuck to his guns and consequently was denied work from publishers like National Periodical Publications, Atlas (which became Marvel), and MLJ (which became Archie). EC continued to hire him–either EC publisher Bill Gaines felt some sympathy for Krigstein’s cause, or he was trying to simply navigate through the great comics scare of the 1950s, or both–but eventually Krigstein had a falling out with Gaines and EC. At that point, he retired from comics in 1962 to spend his life teaching new artists and painting for media outside comics.

Sadly, such a fate has often awaited those trying to prod comics publishers into treating their creatives better. And we also need only look at the next effort to form a comic book union following the Society of Comic Book Illustrators.

The next attempt at forming a union for comic creatives took place in the 1960s, but this time with a focus on writers instead of artists. The story is nonetheless very similar: a lot of talk with little results, unfortunately. The main result would’ve been blacklisting of the creators that signed onto this attempt. Zach Rabiroff for The Comics Journal summarized this trend, writing that, “since the first attempts to form a writers’ union among freelancers at National Comics [now DC Comics] during the 1960s, the story of collective action among the business’ employees has largely been one of false starts, aborted efforts and legal setbacks.”

For Comic Book Artist, Mike W. Barr penned extensively about this attempt to form a writers’ union. He summarized the story of that period in 1968-1969:

Over a period of approximately 18 months, writers whose total experience measured more than a century, many of whom had written for [National Periodical Publications] since the company’s early days, many of whom created some of the company’s most popular and profitable features, left the firm…For two decades it was assumed…that the writers had been summarily fired because they asked for health insurance…The truth seems to be less clear-cut, and more insidious, and heralds the death knell for the Silver Age of Comics.

The politics of this story involve everything we associate with forming a union: proper compensation, profit participation, ownership, and respectful creator treatment.

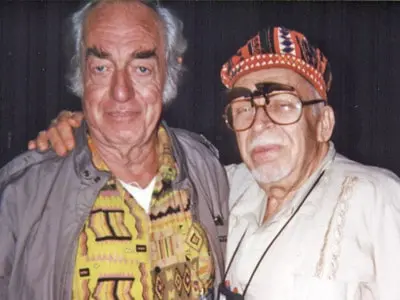

Writer Bob Haney, one of the leaders of this union movement, explained to Barr why he thought the purge happened, which aligns with the commonly accepted truth: “We tried to form a union.” This union included John Broome, Gardner Fox, Bill Finger, Arnold Drake, Kurt Schaffenberger, Dave Wood, Otto Binder, Frane Herron and Mort Meskin, although some of these creators were more involved than others. Fellow member and writer–someone who was very involved in the union–Arnold Drake said “at one point or another it was more than six or eight [members]. I guess it was about 10.”

Haney and Drake

This group of writers, all creators for National Publications, endured a slow accumulation of barbs and thorns that culminated in a few specific interactions that exemplified the poor treatment these writers and other creatives faced. Haney summarized the last straw that pushed him over the edge:

What had prompted the unionization was a terrible meeting that Arnold [Drake] and I had with the publisher [Irwin Donenfeld, National Periodical Publications executive vice-president]…We went in to get a raise…and we went in and hassled this man for an hour, and finally he said something to the effect that he would give a dollar-a-page rate raise, which was ridiculous. And then he said he would only give it to one person at a time, and that I would be the [first] person, which was putting me totally on the spot…And we walked out because we realized this was a joke…The attempt to give [the raise] to one person was to isolate me–or whoever he offered it to–and at the same time to put me on the spot, because if I didn’t take it, nobody would get it. Better he should have said nothing at all, that would have been clear-cut. But this way of trying to isolate us, and divide us, was insulting…We did walk out, as I recall…that prompted us to hold the meetings to form the union.

Haney wasn’t sure if these 1967 meetings happened a few weeks or a few months later. It might have taken more time to organize the meetings or to investigate the requirements for forming a union, like the makeup of full-time employees vs. independent contractors. During this delay, still other creators experienced similar divisive and disrespectful tactics.

Arnold Drake, who according to Haney had been in this meeting with Donenfeld, described a similar story, although he said Donenfeld approached him individually. He told Barr:

Irwin [Donenfeld] and I had words at one point, because when I asked him for a rather substantial raise, and he did agree to give it to me, he then said, “But of course, you’re not gonna mention that to any of the other writers.” And I said, “I’m not going to go out of my way to tell them about it, but I’m not going to lie to them if they ask me.” And that made him quite angry because they worked on a basis of secrecy.

While it’s unclear if Haney and Drake had this meeting with Donenfeld together, or if they had it separately, or if there were two meetings (one with both of them, and one with just Drake), the tactics used by Donenfeld line up perfectly in both recollections: division, secrecy, and cheap incentives offered as if they were large concessions.

Frank Miller’s piece drawn for Barr’s article about this union attempt.

It wasn’t just Haney and Drake who were treated poorly, though, and it wasn’t just Donenfeld who disrespected the employees. Talking to Barr, Kurt Schaffenberger said that the writers were also all “pissed off at Mort Weisinger…He gave them no respect, he gave them nothing but grief.” Schaffenberger offered this story: “I was in Mort’s office one time when he told Bill Finger–a real constructive piece of criticism–he said, ‘I wouldn’t wipe my ass with this script.’”

This type of treatment was the norm, especially from Weisinger, rather than the exception. And this attitude also went hand-in-hand with business practices that rankled the writers, making them feel improperly compensated and recognized. Drake told Barr that the writers’ movement boiled down to a few key issues:

[It] was not about page rates. It was more complicated than that. Page rates were significant, but they did not go to the crux of the thing. The true crux of the thing was the matter of giving the writers some kind of ownership…if not actual ownership, then at least a kind of participation. That was the real issue. What [National Periodical Publications President] Jack Liebowitz did–quite successfully–was to turn it into a page rate issue and order something like a two-dollar raise across the board for everybody…not a significant [raise]…but everybody was very impressed by what they felt was a changing atmosphere, but it did not go to the real root of the problem, which was that writers were to prosper if they were successful in making the company prosper…Partial ownership would probably have been the final goal, but that was way off in the distance…We were interested in some kind of a share of the profits, some means of being rewarded for having done a good job…[A union] would have been the logical outcome [but at the time their] immediate interest was in getting some kind of recognition for the contribution of the creative people. There were a number of [other] requests, and [health insurance] was among them. The best they were willing to do was to allow us to buy our insurance through the company, so we would pay a lower rate, but they weren’t willing to take any part of the insurance.

This laundry list of demands is familiar: the same items pop up in almost every other attempt at unionization or forming another labor organization like a guild.

While these National Publications writers operated as a loose organization, Haney said, “Arnold [Drake] was the man who formulated that sort of thing, [who formulated the demands and dealt with management]. He had more background and experience than I did at the time.” As a fledgling union, they would meet and discuss these issues and demands, then Drake would spearhead the negotiations with the company.

Those negotiations didn’t fare well. Drake recalled that Donenfeld and Liebowitz were willing to grant the writers raises, albeit grudgingly, but refused to give fully paid medical benefits, profit participation, or partial ownership of characters. Drake’s interactions with management illustrated how sharp the divide was: “During negotiations, Jack Liebowitz told Drake, ‘You don’t understand. I’m very sympathetic to the points you’re making. When I was a young man I was a Socialist, too!’ Drake said, though, that ‘the problem was that Liebowitz had a youth of 20 minutes.’”

And management’s attitude only served to increase this divide, to add more roadblocks to the negotiations. Again, speaking to Barr, Drake said that “Liebowitz raised technical and legal questions.” He did admit these were valid concerns to bring up: “Not that there aren’t some significant legal questions. How can you get involved in the matter of ownership of Superman, when it’s been written by so many writers, and when the original writers were screwed out of their ownership to begin with?” Yet, Drake maintains those concerns shouldn’t have stopped them from making progress and finding a solution: “But you know, there are some pretty clever legal minds that are able to solve every damn thing known to man if there is a motivation, if truly both sides want to do it. But that wasn’t the case, obviously.”

Drake explained the real purpose behind Liebowitz raising these concerns:

What they wanted to do was find a legitimate reason for stalling, and that’s what Liebowitz did, successfully. He said, “Let me give it to my attorneys. Let them see if they can work out some marvelous plot that will compensate you without risking our ownership, but you know, that will take a while.”…I was very well aware of what he meant, I knew it was a six-month to a year stall…so [I thought] by the time I got back [Drake had moved to London and later moved back to the US] this thing will probably be resolved–but that’s not what happened at all. What happened was that Carmine [Infantino, the influential artist behind the Silver Age Flash who became National Periodical Publications’ publisher in the 1970s,] moved in at that point, and the whole set-up changed…Once Carmine became the great leader, all those things went by the boards, past relationships went down the drain.

John Broome also saw through this tactic, saying that National Publications executives were ultimately, no matter what they said, “dead set against any kind of compromise” and that negotiations were always just a smokescreen to bide time until the union dissolved on its own.

Unfortunately this approach worked, in part because there were already fault lines in the group that prevented them from fully becoming a union and enlisting the help of more creatives.

The first fault line? Similar to Krigstein’s attempt, the union’s unsuccessful penetration into all creative roles hampered its growth. Unlike Krigstein, though, Haney, Drake, and others in the group never wanted their union to only represent writers. Haney told Barr as much in their interview:

We were trying to get the artists to join…Our big problem was the artists. Because if we didn’t have the artists with us–writers are somewhat more interchangeable than artists in this business…in a way it’s an artists’ medium. If we had three or four of the major artists, we would have had the clout to go into [National Periodical Publications] and get some decent conditions, especially in terms of rate.

Just three artists were ever involved in the group–Kurt Schaffenberger, Mort Meskin, and Carmine Infantino. Haney said that he “was the only [artist] who had the guts or intelligence to recognize that this was where it was at.”

Schaffenberger explained why he joined, telling Barr that at the time, “I was the only artist in the group. One of my closest friends was Otto Binder, and he was one of the leaders of this movement, and he asked would I do this, and I said yes because I always felt that we were getting short-changed, so I started attending the meetings.” Schaffenberger was not involved in any direct negotiations with National Periodical Publications’ management. He said that the writers “were trying to protect me, in a sense, because I was the only artist they’d gotten…so they kept my name pretty much in the background.” It seems somewhat contradictory that they needed artists to help support their movement but they didn’t deploy their only major artist in the group, even if it were unlikely making Schaffenberger a more prominent part of the negotiations would have changed the end result.

The other artists who were briefly involved had even less of a role in the union. “Mort Meskin”, according to Haney, “was kind of out of things by then,” and had largely moved to doing illustration work outside of comics. Infantino did come to one or two of the first meetings, but Haney would say he “was not what I would consider a real stand-up guy.” Drake elaborated on this, saying “I’d invited Infantino to join us,” but Haney recalls that Infantino said, “‘I’m sorry. I’m on the other side.’ This was when he was an artist but was busy wooing the hell out of Liebowitz. Liebowitz [retired] first, and chose–hand-picked–Carmine [as his replacement].”

Carmine Infantino

Additionally, creative people can often struggle to work cooperatively, and that’s just as true for illustrators. Drake said that “there was this feeling on the part of the artists that when you band together, you lose your individuality.” Many artists decided to maintain this perception of individuality, especially in the face of so many obstacles already set against the union-in-the-making.

Drake also focused on another roadblock: the absence of help from other writers’ guilds in traditional publishing. He said, “We tried to bring in the Writers Guild of America (of which I am a 25-year member).” Yet their appeals brought no immediate aid; they were told “to come to them when we were fully organized and then they would help. Which is like a life-guard shouting to a drowning man, ‘I’ll save you just as soon as you’ve swam to shore and hung up your suit to dry!’” The group never organized enough to suit the WGA, so they never received any help from them.

But perhaps the most persistent obstacle to creator unionization is a general hesitancy to rock the boat, lest creators compromise what they themselves view as an enviable position in an aspirational industry. “It strikes me as [being like] the World Wrestling Federation, and [Vince] McMahon, and Hulk Hogan,” Shaun Richman said. Shaun Richman is a labor historian and former union organizer who teaches at Empire State University. Richman elaborated on this comparison, saying that “it’s kind of like: the work is awful, you’re not getting respected, you’re not getting compensated for what you’re doing. But you aspired to be here since you were a kid. And now that you’re here, it’s a really conflicted thing.” Comics, and other creative industries, often rely on this internal conflict.

Nevertheless, Richman draws a comparison to the celebrated strike among animators at the then-non-unionized Walt Disney Productions in 1941, which left a substantial effect in its wake. “It’s Disney,” Richman said. “If you love animation, that’s the place you wanted to be”, much like professionals working in the comic industry. Richman highlighted an important difference, though: “And yet, those artists, those writers, they all went on strike. They did the thing. And partly it was during an upsurge of worker organizing because of the war, and that’s essentially the answer: it’s got to be part of the social movement. It’s got to be part of ‘now is the time.’”

Facing all these obstacles, Drake’s group discussed one last attempt at having them and their demands taken seriously: strike. With management stalling and turning a deaf ear to the group’s demands, some members suggested a strike. Haney recalls Drake being the first to say so. Haney’s response, which he admits, “does not reflect any credit on me,” was to refuse in light of their preexisting recruitment problem:

We had no artists with us. I said, “Arnold, if we get two or three of the major artists with us, I promise you, I’ll go out with you. We’ll walk.” And we could have shut them down, because you cannot lose four or five major writers and three or four major artists…They always had a terrific deadline problem there.

A strike of even a handful of major writers and artists would’ve disrupted the company’s production significantly. But that strike wasn’t to be. After the strike idea was rejected, Haney said, “that’s kind of when the union fell apart.”

He offered one final reflection on this strike gambit:

Maybe [Drake] was right in the long run. You see, I took a calculated gamble. I thought, “Well, if we don’t have the artists, writers they can get quicker and easier, and probably just go right along, and we’ll be done for it.” [Still] I thought, “What the hell, I’ll do it if we have a chance of winning it.” [But] I did not think we had a chance…Plus, I was building my house…and the strike was coming at the very worst time for me personally. I had more at stake than anyone at the ‘union’ meetings, so I was being asked to take the biggest risk…At that point, the only guys who would have walked would have been me, Arnold, and two or other guys. Gardner, I guess. So it didn’t happen. That’s a very crucial part of the story.

National Periodical Publications did end up replacing them and other major writers. Haney said, “So I guess I was right, in the abstract, but sometimes I wish I had just been in a position or had the balls to just [say] ‘Fuck you guys.’”

He emphasized how the artists he needed to pull the trigger on a strike later expressed regret at not joining their group: “Just a few years [after the group dissolved] prices began to rise, costs of living began to rise, there were no big raises for the artists, and they began to hurt.” This also aligned with National Periodical Publications letting go of many of their veteran creators and replacing them with new creators. “And [the artists] sort of came back to us and said–some of them did, anyway–‘Hey, maybe you guys were right.’” But in Haney’s view it was too late. “The corporate changeover took place, and Carmine came in, and all the other changes [in staffing and the business]…and it became kind of a different ball game…We said, ‘Well, if we had you guys [then] we could have maybe had some clout.’”

Page from The Doom Patrol #121. Originally Drake and artist Bruno Premiani would be pictured, appealing to the reader to avoid cancellation. Irwin Donenfeld (National Periodical Publications executive vice-president) replaced Drake’s image with editor Murray Boltinoff. Drake called it “petulant retaliation” for the union.

Most of the new generation of writers also didn’t know the circumstances of their hiring, and when they found out about the previous generation’s treatment and failed labor struggle, they often expressed regret. Mike Friedrich, who started working at National Periodical Publications in 1967 said, “I did not hear [the rumor of firing] until Bob Haney, or Arnold Drake, or somebody [else] wrote a letter to The Comics Journal in the late [s]eventies…and that was the first I ever heard of it.”

Friedrich did say that some of the firing was probably due to the quality and old-fashioned nature of the previous generation’s work. He said he “saw Gardener Fox scripts–typical scripts–they were literally 90% copyrighted by the editor. So there is some validity, in my mind, to Schwartz’s perception that Fox [and others of his generation were] just not producing adequately…and it was reasonable for the editor to pursue [a younger writer].”

He did admit that, “As an older person now, I feel I was probably fairly arrogant, but now I have a lot more respect for what they were doing than I did when I was 18.” He also admits that, even if the quality issue was part of the reason the writers were pushed out, it is probable that their demands also were part of the reason: “Now that I have 20 years of experience with [comic book] management, I believe that management is capable of doing anything.”

Friedrich is probably correct that it is a combination of creative and business factors that contributed to the writers purge, and that the union talk was the final straw that pushed National Periodical Publications to fire the older generation of writers. What is clear is that the Silver Age writers clearly recognized a flaw in the system, a flaw that benefitted publishers and disadvantaged their creative employees. Thus, a new generation of writers and artists would also come to have similar grievances, and they too would–in fits and starts–try to win better treatment.

In early 2000, Drake offered a final reflection on their failed union experiment:

It was apparently an idea whose time had not come. Maybe it’s right now, but it doesn’t look like anybody’s going to bother to do it. Now they’re making the mistake of saying, “We don’t need it, we’ve got everything that we want.” That’s dumb. What you need is recognition. You need to be dealt with as a group, not as individuals…What the [freelancers] have gained hasn’t been taken, it has been given to them–and that which is gratuitously given to you can be just as easily snatched back. So if the whole field is going to become truly legitimate, the writers and the artists will one day get together and take what’s rightfully theirs, by speaking with a single voice, instead of trying to go in and negotiate one by one.

Drake was right–it was an idea whose time had not come. But it eventually would, even though it would take a few more failed attempts, not to mention a large legal obstacle.

That obstacle concerns the 1935 National Labor Relations Act and how it treats freelance workers, independent contractors who labor under work-for-hire conditions. In an article for Comics Beat Andrea Ayres quotes their legal expert Jeff Trexler on a summary of this issue. Trexler told Ayres, “The National Labor Relations Act protects employees, not independent contractors,” and that distinction is important. “Whereas a union has a legal right to engage in collective bargaining and to strike, freelancers who try to do that can be fired or blacklisted without penalty.” Even more damaging, “freelancers refusing to follow the terms of their contract could be found in breach and liable for damages.”

Doubling down on this restriction, the Taft-Hartley Act of 1946 made this distinction clearer. For Bleeding Cool, Rich Johnston wrote, “The famous Taft-Hartley Act of 1946 explicitly excluded ‘any individual having the status of an independent contractor’ from unionizing to the section that already excluded domestic and agricultural workers from being able to exercise that right.” The National Labor Relations Act made it clear that full-time employees were the only ones protected, especially when participating in collective bargaining. The Taft-Hartley Act made it clear that independent contractors were not only not protected in this action: it was illegal for them to do so.

Some legal experts don’t completely agree with the ways these laws have been interpreted and implemented, especially in the classification of work-for-hire as being synonymous with independent contractor. When speaking to The Comics Journal, legal expert Shaun Richman said that while work-for-hire creators are now classified as independent contractors, that status is more flexible, and more political, than most think. “I would note that case law on this sort of thing swings wildly between Democratic and Republican administrations,” Richman said. For example, he says, “in the Biden administration, you have really one of the best Labor Departments, and one of the best National Labor Relations Boards, that you’ve had since I’ve been alive. So who knows, if you put a case in front of them, how they would rule.”

Further complicating this gray area is the practice of “permalancing”. For The Comics Journal, Ian Thomas defines permalancing as “the practice of depending on someone technically classified as a freelancer to work full-time (or more than full-time).” He writes that they are “generally expected to be available during office hours and to perform duties equal to or greater than those of full-time staff.” Despite this full-time status in everything but name, they still receive no benefits or protections. Maybe, as Richman thinks, if a case was brought to the National Labor Relations Board, this practice would be revised to give permalancers and other freelancers more rights.

Even if some of these practices could be ruled illegal, Richman did add that the threat of legal challenges to unionization on the part of employers is a deterrent against unionization regardless of legality. He points out rideshare companies make this threat even though he thinks it’s a shallow one: “Uber and Lyft do this. And in any common sense definition, if you’re driving a car on the Uber app or the Lyft app, you work for Uber or Lyft.”

Noted journalist Ari Paul (who has written for The Nation, The Guarding, Jacobin, and more) also takes issue with the idea that work-for-hire creators can not have a union working for them. For Jacobin, he wrote against “the fiction that there’s no space for real unions in a freelance economy.” To disprove that fiction, he describes how ‘construction unions and entertainment industry guilds are comprised almost entirely of freelance workers who travel from gig to gig, with the union acting as both a sort of exclusive employment agency and a channel to protect wages and provide benefits a freelancer wouldn’t otherwise have.” And, even if they aren’t able to engage in collective bargaining, Paul tells us that we have seen this approach successfully support workers.

For instance, Larry Goldbetter, president of the National Writers Union, has said that “in the last five years we’ve settled three mass grievances at three publishers. Being part of a larger union with a legal, legislative, and organizing department gave us more reach.” The Freelancers Union also offers another example. Although it does not participate in collective bargaining deliberations with employers, it does help with healthcare, insurance, and other provisions that a freelancer may find harder or more expensive to secure. It should be noted that, despite being called a union, the Freelancers Union operates more like a guild or a benefits marketplace. In contrast, the Editors Guild uses more traditional collective action to regain some workers rights. In the 2010s, they won back jobs for Shahs of Sunset editors who had been fired for unionizing. “Old-fashioned picketing and solidarity secured a fairer workplace,” lauded Paul, and it was done for freelance workers and not just full-time employees.

Other experts agree that these industries and their labor organizations can be a good model for comics. Speaking to Ayres, Sasha Bassett–a PhD student in sociology and an instructor at Portland State University who has researched worker satisfaction and workplace climate in comics–said that “another example can be found in a recent development with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), who has helped establish the IWW Freelance Journalists Union.” They offer a model for how “comics could go a similar route and have all freelancers work within the same bargaining unit, rather than with smaller groups oriented around individual jobs.” She does add a qualification, though, that we’ve already seen:

At this point, I think the biggest obstacle for workers themselves is the culture of silence around their conditions – folks seem very reluctant to say anything negative out of fear they might be blacklisted. I think a union (or comparable workers’ organization) would certainly be a good step in the right direction on addressing this.

Even with these large legal obstacles, sometimes a culture of fear and silence is the main reason comic creators don’t organize. Of course, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t address these legal issues.

In fact, many simply question the appropriateness of this legal framework, especially in today’s society. Ayres makes this clear in her article for Comics Beat when she wrote that “the gig economy has blurred the line between employee and employer. It’s another one of those instances where the law hasn’t caught up with modernity.”

But it’s not just comic journalists that have raised this alarm. Even bastions of free-market thinking, like Forbes, have brought up this issue. For Forbes, Elaine Pofeldt asked this question that cut to the heart of the issue: “Why do American laws still assume that the default situation of workers is a full-time job with benefits? Our laws are badly dated, leaving independent workers at a profound disadvantage when it comes to the basic necessities of life.” And those laws lead to real consequences, as she points out: “Why is there a giant group of hard-working taxpayers who lack the basic safety net we give to other workers?”

Pofeldt goes on to explain that even though more Americans are self-employed than when these laws were first created and their numbers are expected to climb, our country is still operating under the workplace conditions of one hundred years ago. Ultimately, she believes that “we shouldn’t need [traditional unions, guilds or non-traditional groups like the Freelancers Union] to take the lead in fixing this gigantic problem–which affects millions of people and is likely to touch many more in years to come.”

1970 saw the next effort to fix these gigantic problems within the comic industry, although it too would have a narrower scope and more meager gains than comic creators and labor activists would like. That year, the Academy of Comic Book Arts (ACBA) was formed by Stan Lee and other comic creators. Lee wanted it to be an analog to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, to serve as a way to honor creators like the Oscars/Academy Awards did. Such awards were distributed until 1974.

Before long, Neal Adams and others tried to transform it into an advocacy organization focused on creators’ rights. Neal Adams was one of the artists who revolutionized superhero comics in the seventies, implementing dynamic layouts and anatomical correctness, most notably in his and Denny O’Neil’s famous Green Lantern/Green Arrow run that tackled real-world issues. As his fame grew, Adams would also become a notable proponent of creators rights in the comics industry. Steve Englehart told Jon B. Cooke in a Comic Book Artist interview that “Neal was one of the movers and shakers, and we were all Young Turks, though we didn’t know exactly how screwed we were getting by the companies.”Englehart offered an explanation as to how creators got into this predicament:

They came in and asked, “You want to work in comics? Here’s what we’re paying.”[And we took it because] it was the only game in town. Nobody said, ‘We can get a better deal elsewhere’, because there was no ‘elsewhere’; it was just the way the comic business was. In later years, we began to realize that people who are working in other publishing media were getting royalties, health care, and things like that, and over the years those things have happened in comics [partly due to activism by the ACBA and other groups].

Cooke, also writing for Comic Book Artist, would say that the organization changed from being “a self-congratulatory organization focused on banquets and awards” to one where the “Angry Young Men in the industry…educated, informed, and gutsy artists and writers, self-confident and filled with a strong sense of self-worth,” fought for rights in a way that few dared. “Lee was aghast,” writes Stan Lee’s biographer Abraham Riesman. Lee said of the endeavor, “I wasn’t interested in starting a union … so I walked away from it.”

Others walked away too, and by 1977, the ACBA was defunct. This was largely because of this division between those who wanted it to focus solely on its original purpose, awards, and those who wanted it to shift focus to creators rights. Ultimately, it didn’t win any official battles, but it joined the voices that had, would, and will shout against worker mistreatment.

Ultimately, the ACBA’s legacy coincided with several landmark events in the industry concerning some of the most influential creators. It’s worth a brief detour because it shows the typical way in which comic creators have had to fight for their rights without an effective union.

With the first Superman movie’s premiere on the horizon in 1978–and his creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster receiving no creator byline in the comics, and no money from the movie–one of the biggest comic creator rights battles would ensue. In 1975, after getting nowhere in negotiations with National Periodical Publications about a share of the upcoming movie’s profits, Siegel released a nine-page press release where he (literally) cursed the movie. “Why am I putting this curse on a movie based on my creation SUPERMAN? Because cartoonist Joe Shuster and I, who co-originated SUPERMAN together, will not get one cent from the SUPERMAN super-movie deal.”

After reading this release, Neal Adams recalls telling those working with him in his studio: “I am going to see to it that this gets fixed, and I am not going to stop until it does. So if any of you want to help me, I’d appreciate the help. If you don’t want to help me, there’s no obligation.” Since Shuster and Siegel weren’t part of a union, they had to rely on the goodwill of fellow professionals.

Former Batman artist Jerry Robinson, also outraged upon reading this letter, joined Adams and lawyer Edmund Preiss in taking the fight to National Periodical Publications. Paul Levitz recalled how the three men worked as a cohesive unit. “Jerry was probably the more suave negotiator, Ed the wise lawyer…but Neal roared the loudest. And they won.”

Adams brought Siegel out to New York, where they appeared on every talk show that would have them. The negative publicity was enough for National Periodical Publications to acknowledge Siegel and Shuster as the creators of Superman and give them an annual stipend of $20,000 as well as health benefits, not to mention the return of the “created by” Siegel and Shuster byline after 343 Action Comics issues where it had been absent. We can and should laud this victory, but we should also acknowledge that it’s a victory that can not often be repeated without a larger and more formal group like a union.

Shuster, Adams, Siegel and Robinson

Just as National Periodical Publications settled this dispute and was officially renaming themselves DC Comics, a similar conflict was occurring at Marvel. Jack Kirby, co-creator of most of Marvel’s most well-known Silver Age characters, was fighting for the return of his art, creator credit, and other associated rights. At the time, Marvel had recently started to return newly completed art to the artists, but they did not return old art, including most of Kirby’s Marvel work.

Marvel was willing to offer a small concession (or, looking at it another way, a robbery wrapped in a concession): they’d return Kirby’s art if he signed away all rights to the Marvel characters he created. Additionally, Marvel could also claim any of Kirby’s art that was found following the completion of the agreement. At this point in 1984, the company was only able to account for 88 pages of the more than 8000 pages of art Kirby had done for Marvel between 1960-1970, meaning that he’d only be signing the form for 1% of his work from that decade.

By the summer of 1985, this standoff became public knowledge when The Comics Journal broke the story. They continued to cover the story in subsequent issues, and in an February 1986 editorial, “House of No Shame”, TCJ Editor/Publisher Gary Groth wrote that “You don’t need to have grown up reading Jack Kirby’s work to recognize that Marvel’s treatment of him is criminal.” But they didn’t stop with that editorial. The editorial was just one part of a Kirby-themed issue “dedicated to swaying Marvel’s heart, if indeed the corporation has one.”

This dispute also surfaced during comic conventions, conventions tangential to the world of comics (like fantasy conventions) and even penetrated the comic media bubble. Some Los Angeles TV and radio stations picked up the story. Even DC sent The Comics Journal an open letter scolding Marvel for failing to follow DC’s example in returning art (although it must be said, DC was returning art to avoid paying sales tax on it, something they’d have to do if they kept the physical art they reproduced in comic form. Perhaps unsurprisingly, DC wasn’t taking this stance out of some moral obligation).The effect, Michael Dean wrote, was that “Kirby became a comics cause célèbre and [Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief Jim] Shooter and Marvel found themselves in the middle of the worst public relations disaster in the company’s history”.

Marvel and Kirby continued their fight over the next few years, but eventually Marvel acquiesced to many of Kirby’s demands. In May 1987, Marvel dropped their demand that Kirby sign the document and instead had him sign a short form that had been amended to address his concerns. Details of this form aren’t known, but Kirby’s lawyer Greg Victoroff told The Comics Journal that “Jack got just about everything he wanted,” including 1,900 pages of his art instead of the originally offered 88. Kirby’s creator credit eluded him, though: he wouldn’t live to see it, but his family won that right in 2014.

Kirby wasn’t the only one to reap the benefits of this battle. In May 1987, Marvel returned Neal Adams’ art without making him sign even a short form. Still, they weren’t legally required to make this concession, and they weren’t legally required to maintain it the day after they handed Adams his art. They could easily change course later. A union or guild would be needed to make this legally binding, but Kirby and Adams just had themselves and the backing of a small but vocal fanbase and press. Returning Adams’ artwork, in truth, was probably just to avoid another PR disaster at his hands.

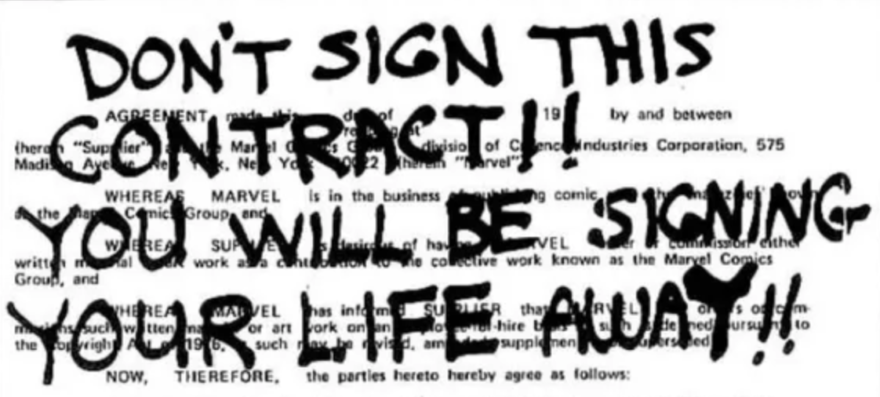

Adams’ earlier fight with Marvel, and the industry at large, came about right around when Kirby started fighting for the return of his art. In his article, “It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane…No, It’s a Union!”, Kennedy writes that the larger labor battle was renewed by the 1978 revisions in copyright laws, which required something in writing that documented what rights the creators would turn over. “Panicked, Marvel Comics began sending out one page contracts to freelancers working at the company that would require them to sign away all rights in perpetuity to the company,” Kennedy wrote.

Fresh off his victory for Siegel and Shuster, and brimming with outrage at this latest example of the industry’s continued mistreatment of creators, Neal Adams sent a flier to his fellow creators that warned, “DON’T SIGN THIS CONTRACT!! YOU WILL BE SIGNING YOUR LIFE AWAY!!” Emphasizing his point to the press, Neal Adams told The Comics Journal, “Anybody who signs that form is crazy…. You dangle a carrot in front of the artists’ faces, saying, ‘If you want your art, sign this form.’ It’s not true; you don’t have to sign it.” But Adams wasn’t content with just a press release or warning–he wanted change.

To spur his colleagues into action, Adams invited big name creators to a meeting at his studio with the intent of forming a group that would fight for creator’s rights. This group became the Comic Book Creators Guild. Its members included the heavy hitters of the day: Paul Levitz, Jim Shooter, Frank Miller, Walt Simonson, Chris Claremont, and more alongside Neal Adams himself. Their May 7, 1978 meeting was even attended by The Comic Journal’s editor Gary Groth. Groth published his 13 page coverage of this meeting in The Comics Journal #42, including a transcript of the meeting, which revealed both their idealistic demands and the tumultuous controversies within the group.

Although the Guild would have many disagreements over their short life, they did initially align on recommended page rates. Writing for Comics Alliance, Janelle Asselin estimated that:

[A]djusted for inflation, those rates today would be:

Artists: $1080 [$300 in 1978]

Writers: $360 [$100 in 1978]

Letterers: $144 [$40 in 1978]

Colorists: $252 [$70 in 1978]

Asselin pointed out that those rates “dwarf most creators’ rates today…In fact, there are a lot of creators in comics today who don’t even make as much as the 1978 rates” they demanded, without adjusting for inflation. These rates were never a realistic goal; it might have been part of the tried-and-true negotiating tactic of starting with a high offer and then meeting in the middle.

Increased, standardized page rates weren’t the only demands the Guild outlined. They also wanted 25% of the fees for foreign first North American publication rights, and 50% of the fees for (domestic, nonforeign) first North American publication rights. Like the page rates, these percentages were idealistic and did not add much momentum to the Guild.

The Guild would soon shut down, with Groth’s article and transcript revealing debates and echoes of disagreements we’ve already seen. The first meeting, according to Groth’s transcript, “reveals a room that was a boringly toxic mix of apathetic, confused and angry about weirdly specific things.” William Gatvackes for Film Buff Online wrote that the meeting “could best be described as chaotic,” both in volume and etiquette: “Groth reports many instances of people talking over each other.”

This chaos led to a lot of misunderstanding and dissatisfaction with the Guild. Writer Bill Mantlo explained at the time that “a guild isn’t strong enough. We need a union.” On the flip side, John Byrne said he wouldn’t join the Guild because “it stank of unions.”

“Even members of the ad hoc [Guild] Committee don’t seem to talk to one another, or to even know what the Guild’s progress is.” Groth wrote. “The ad hoc Committee members [also] do not appear to be thoroughly aware of the issues.”

And there was even more disunity than that. Creators for each role in the production of comics–pencillers, inkers, colorists, letterers, and writers–couldn’t agree how valuable each member was to the creative process, leading to demands to revisit and revise the recommended page rates. Gatvackes underscored this division when he wrote that they were quibbling over “bones of contention”, like “whether or not inker and colorists, who depend on pencillers for their work, and letterers, who depend on writers for their work, deserve the same kind of rights to their works” as writers and pencillers. Even at the time, this was noticeable. In his initial coverage, Groth wrote that “major figures in the proceedings, including Adams, were dismissive of letterers and essentially anyone not contributing to line art or scripting.”

Other creators, like writers Roy Thomas and Denny O’Neil, weren’t confident the industry was stable enough and publishers profitable enough to pay the rates the Guild demanded. In the transcript, creators can be heard arguing how many books the companies “really sell each month” and over how secure the industry was.

And, as we saw with the National/DC union, most of the legendary artists in the field (John and Sal Buscema, Gene Colan, and Curt Swan, for example) didn’t join the Guild, even though Adams tried to enlist them. These artist refused because they were too well established in the industry and didn’t want to risk joining the new organization and possibly being blacklisted. Colan is quoted in The Comics Journal as taking a “wait and see attitude” to the guild. “I’m associated with Marvel and they’ve treated me pretty decently and I don’t want to go off on a limb,” Colan said. “It’s a little risky at this point and I’m not going to make any waves.” Gatvackes argued that this was an expected result. While Adams relied on work outside the comic field to make a living–advertising work, for instance–other creators didn’t have that lucrative side hustle and didn’t think they could jeopardize their livelihood.

Such disagreements led to a swift dissolution of the Guild. In a 2019 article for The Comics Journal, Austin Lanari gave a snapshot of this journey: “[The Comics Journal] report [about the Comics Guild] had almost-top-billing on the front cover of the issue, only being beaten out in prominence by the words ‘STAN LEE INTERVIEWED!’” But the next mention wasn’t until 10 months later, and it was only mentioned with “a stream of small news blurbs in the opening pages, just before the letters to the editor but about nine pages after a report about the fact that Howard the Duck was going to start wearing pants.”

Although the Comic Book Creators Guild faded quickly, it might have helped creators in the long run. DC Comics instilled its royalty program in November of 1981 and Marvel started one less than a month later. The system would give creators who worked on books that sold over 10,000 copies a percentage of the sales. Neal Adams said in 1982 that, partly because of the Guild, “companies [started] offering better conditions for their artists…health benefits [in addition to] raising their rates, agreeing to pay reprint money, [and other] incentive programs, like if you stay on a book so long you get a bonus.” In Adams’ opinion, soon after the Guild’s short life, “The companies started to treat the freelancers better.”

However, these gains aren’t seen as a winning record for the Guild by many, because these gains depended on publisher goodwill and still left the door wide open for individual battles instead of opening a path for true collective action. Though people often ask about what went wrong with the Guild, Lanari wrote [italics in original], “very little, if anything, has been said about what it would have taken for things to go right.” He outlined three further questions that need to be asked: “What balance of compensation, rights, and forfeiture provide fair recompense to creators, both immediately and over time? Question two: “What is an effective vehicle for creator consensus of these needs?” And question three: “How do creators get a seat at the table along with publishers in establishing and normalizing those agreed-upon standards of fairness?”

Lanari’s answer to this conundrum is straightforward: the only way to create agreed-upon demands with creator consensus and getting a seat at the table in a normalized process is through a union:

The fact of the matter is that, in this country, without a labor union, you cannot answer any of these questions. There is no labor autonomy without a union because any group, no matter how disciplined, cannot and will not stick to a set of standards if they all have to negotiate with the boss privately. People will sell out. People will be taken advantage of. Loosely agreeing on terms is not collective addiction: it is distributed folly.

Ultimately, Lanari believes that “unionization is the best legal path to just compensation…Bill Mantlo said it best in issue #42 of The Comics Journal, 40 years ago. ‘A Guild isn’t strong enough. We need a union.’”

Lanari isn’t always clear on the specifics, such as how to actually embrace the contractor status within a union that forces publishers to recognize work-for-hire contractors as employees with whom they need to collectively bargain, he still offers some ideas.

For instance, he points out that California Labor Code 3351.5c states that the legal definition of Employee includes “any person while engaged by contract for the creation of a specially ordered or commissioned work of authorship in which the parties expressly agree… that the work shall be considered a work made for hire.” This means that anyone signed to a work-for-hire-contract by a company based in California (which includes Boom! DC, and IDW, for instance) should have their business cover, at least, unemployment insurance and workers comp.

All comic publishers aren’t based in California, though, so it doesn’t work as a basis for collective bargaining industry-wide, especially since Lanari admits that in California “there is essentially no functional difference between for a worker in terms of rights forfeited between being an employee and being a work-made-for-hire contractor…except for that whole ‘employees have benefits and are legally allowed to unionize and collectively bargain.’”

After Lanari admits this, he says that there is one option for employees to form a union and collectively bargain, and that option is in the model provided by Hollywood guilds like the Writers Guild. Lanari hopes to form a group of independent contractors that can collectively bargain along this model, side-stepping the work-for-hire obstacle. There is precedent here as well, in that film and TV studios initially refused the Writers Guild’s right to collectively bargain for similar reasons that comic publishers have done so in the past.

One of the studio’s first rebuttals was that the writers are “free to develop” their own work, so the studio shouldn’t be beholden to the writers since the writers aren’t beholden to the studios. However, the Writers Guild fired back that “screenwriters work under the direction of a producer or an associate producer” and that they “may be given the result of another writer’s work in developing a story” and screenplay. This all means, the Guild concluded, “that the writer’s work is subject to the critical examination and close scrutiny of the producer and that the producers’ word is usually final as to the contents and ultimate form of the script.”

Lanari argues convincingly that this is similar to how creatives work in comics. The creative has to answer to the series editor, other editors, the publisher, and more, regarding how their story fits in the canon of the publisher’s universe, what they are and are not allowed to do with certain characters, and so on. These conditions are similar to what a screenwriter faces when working with producers and studios.

That’s not the only argument the studios, publishers, and other companies have launched against contractors banding together in a unit to collectively bargain. Full-time employees, they’ve suggested, are required to “maintain office discipline,” but writers and other creatives in Hollywood can be removed from a project (or canceled) due to failure to meet a public standard of decorum, a variation of “office discipline” that is a result of a work culture in which many full-time employees don’t go into an office.

With these and other examples, Lanari makes the argument that the control exercised by the employer is the key factor in whether a worker is an employee with collective bargaining rights or an independent contractor without those rights. UC Berkeley law professor Catherine Fisk agrees, saying “It doesn’t matter whether someone works on a series of short-term contracts or is labeled a freelance writer. What matters is the degree of control exercised by the putative employer.”

Fisk admittedly is in favor of revising the way we look at work-for-hire labor in a way similar to Forbes’ Elaine Pofeldt. In Fisk’s 2018 paper for the University of Chicago Legal Forum, “Hollywood Writers and the Gig Economy”, Fisk wrote that “the notion that larger numbers of workers are independent contractors not entitled to unionize or to the protections of employment law is a product of twentieth-century legal categories that are a poor fit for twenty-first century companies and labor markets.” Still, Fisk thinks overhauling our labor laws to cover independent contractors is not a realistic solution because of the work involved. Fisk instead says we should follow the Writers Guild path and that ensuring “collective bargaining by independent workers today is an important and effective way of accommodating employer flexibility with employee protection.” This is the approach Lanari supports, although he wants it done by a group called a union, not a guild. Given that he wrote his article in 2019, he wouldn’t have to wait long for this to be a reality for some comics professionals, but there would be a few more false starts before that group was formed and reached the finish line.

“The Cost of Comics: A History of the Comic Book Labor Movement” will conclude on the Cartoonist Cooperative Journal on December 22 .

CJ Standal has taught and written about comics for years (chronicled and collected in Outside the Panels: Comics, the Classroom, and the Creative Life); he also has written comics of his own, including Rebirth of the Gangster, published by CJSP, and B.A.E. Wulf, published by Markosia. He is currently finishing his first fictional prose novel, Mapping Mythland.

Bibliography

Adolphus, Emell Derra. “Image Comics Union Ratifies First Contract.” PublishersWeekly,

PWxyz, LLC, 3 Mar. 2023, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/

comics//article/91682-image-comics-union-ratifies-first-contract.html.

Asselin, Janelle. “1978 Creators Guild Wanted Rates That People Still Don’t Get.”

ComicsAlliance, Townsquare Media, Inc., 11 May 2015, www.comicsalliance.com/

Ayres, Andrea. “Will Comics Ever Get a Union? Sasha Bassett Plans to Find Out.” The Beat,

Superlime Media LLC, 10 Mar. 2020, www.comicsbeat.com/sasha-bassett-comics- union/.

Carlson, Johanna Draper. “Drawn & Quarterly Workers Unionize.” ICv2, 17 Nov. 2023,

www.icv2.com/articles/news/view/55629/drawn-quarterly-workers-unionize.

Colbert, Isaiah. “First Manga Worker Union Forms Amid Alleged Union Busting.” Kotaku, 31

May 2022, www.kotaku.com/seven-seas-entertainment-manga-union-united-workers-in-

Cooke, Jon B. “A Spirited Relationship.” Will Eisner Interview – Comic Book Artist #4 , Two

Morrows Publishing, www.twomorrows.com/comicbookartist/ articles/04eisner.html.

Cronin, Brian. “How Neal Adams Fought for the Most Important Superman Byline Ever.” CBR,

Comic Book Resources, 6 May 2022, www.cbr.com/neal-adams-superman-fight-siegel- shuster-byline-credit/.

Dean, Michael. “Kirby and Goliath: The Fight for Jack Kirby’s Marvel Artwork.” The Comics

Journal, Fantagraphics, 1 Oct. 2021, www.tcj.com/kirby-and-goliath-the-fight-for- jack-kirbys-marvel-artwork/.

Doherty, Brennan. “Why the US Embraced ‘Strike Culture.’” BBC News, BBC, 28 Sept.

2023, www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20230927-how-strike-culture-took-hold-in-the-us- in-2023.

Elbein, Asher. “Marvel, Jack Kirby, and the Comic-Book Artist’s Plight.” The Atlantic, The

Atlantic Monthly Group, 1 Sept. 2016, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive

/2016/09/marvel-jack-kirby-and-the-plight-of-the-comic-book-artist/498299/.

“Freelancers Union: Mission.” Freelancers Union, 25 July 2023, www.freelancersunion.org/

Gatevackes, William. “Comic Creator Credit: Why Not Unionize?” FilmBuffOnline, 22 Oct.

2021, www.filmbuffonline.com/FBOLNewsreel/wordpress/2021/09/10/comic-creator-

George, Joe. “Neal Adams and the Fight to Unionize Comics.” Progressive.Org, 5 May 2022,

www.progressive.org/latest/neal-adams-fight-to-unionize-comics-george-220505/.

“A Guild for Comic Book Creators?” ICv2, 17 Dec. 2012, www.icv2.com/articles/comics/view/

24624/a-guild-comic-book-creators.

Harper, David. “The House of ‘The Walking Dead.’” The Ringer, Spotify AB, 1 Feb. 2017,

www.theringer.com/2017/2/1/16041010/image-comics-25-year-anniversary-the-walking-dead-e4774b7bffcd.

Jackson, Gita. “The Image Union Is the Future of Comics.” Vice, Vice Media Group, 22 Nov.

2021, www.vice.com/en/article/y3vdbx/the-image-union-is-the-future-of-comics.

Johnson, Destiny. “Image Comics Will Not Voluntarily Recognize Union.” KGW8, KGW-TV, 14

Nov. 2021, www.kgw.com/article/entertainment/nerd-news/image-comics-union/283-632

71a11-5e86-4c72-ae40-59e5d5b0f24f.

Johnston, Rich. “Comic Book Workers United Is Now America’s First Comic Book Union.”

Bleeding Cool News And Rumors, 7 Jan. 2022, www.bleedingcool.com/comics/comic-

book-workers-united-is-now-americas-first-comic-book-union/.

Johnston, Rich. “Comics Creators – Together We Will Stand?” Bleeding Cool News And

Rumors, 7 May 2010, www.bleedingcool.com/comics/recent-updates/comics-creators-

Johnston, Rich. “So Why Are There No Comic Book Unions Then?” Bleeding Cool News And

Rumors, Bleeding Cool News, 21 Oct. 2018, www.bleedingcool.com/comics/comic-book -unions/.

Kennedy, Hank. “It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane…nNo, It’s a Union!” Tempest, Tempest Magazine, 9

Mar. 2022, www.tempestmag.org/2022/03/its-a-bird-its-a-planeno-its-a-union/.

Knight, Rosie. “The Comics Industry Has Left Creators to Drown, So Some Are Building

Lifeboats.” Polygon, Vox Media, 13 Oct. 2023, www.polygon.com/23914388/comics- broke-me-page-rates-creator-union-cartoonist-cooperative-hero-initiative.

Kleefeld, Sean. “The Creator’s Bill of Rights.” Kleefeld on Comics, 20 May 2021,

www.kleefeldoncomics.com/2021/05/the-creators-bill-of-rights.html.

Lanari, Austin. “Unionize Comics: The Comics Guild and the Possibility of Collective Action.”

The Comics Journal, winter 2018, pp. 120–137.

“Labor Unions.” National Museum of American History, 2023, https://americanhistory.si.edu/

american-enterprise-exhibition/consumer-era/labor-unions.

Lauer, Jonathon. “The History of Image Comics.” The Nerdd, 27 Aug. 2020, www.thenerdd

.com/2018/11/30/the-history-of-image-comics/.

McCloud, Scott. “The Creator’s Bill of Rights.” ScottMcCloud.com, www.scottmccloud.com/4-

McMillan, Graeme. “The Comic Book Industry’s Next Page-Turner: Union Organizing.” The

Hollywood Reporter, 22 Nov. 2021. www.hollywoodreporter.com/business/business-

news/the-comic-book-industrys-next-page-turner-union-organizing-1235044157/.

McMillan, Graeme. “Image Comics’ Workers Union: Everything You Need to Know About

Comic Book Workers United.” Popverse, 22 Sept. 2023, www.thepopverse.com/image

-comics-union-comic-book-workers-united-update.

McQuarrie, Fiona. “Unionizing Comics.” All About Work, 28 June 2019, www.allaboutwork.org

/2019/06/27/unionizing-comics/.

Paul, Ari. “A Union of One.” Jacobin, 2023, www.jacobin.com/2014/10/freelancers-union/.

Pofeldt, Elaine. “A New Safety Net for Freelancers.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 25 June 2014,

www.forbes.com/sites/elainepofeldt/2014/06/25/a-new-safety-net-for-freelancers/?sh=24

Pulliam-Moore, Charles. “Ex-Marvel Editor: ‘Self-Defeating Conclusions’ Prevented

Unionizing.” Gizmodo, 23 Nov. 2021, www.gizmodo.com/ex-marvel-editor-alejandro-

arbona-says-self-defeating-1848112042.

Rabiroff, Zach. “At Image, Comic Book Workers United Takes Another Step in a Long Union

Walk.” The Comics Journal, Fantagraphics, 12 Mar. 2023, www.tcj.com/at- image-comic-book-workers-united-takes-another-step-in-a-long-union-walk/.

Reed, Patrick A. “Today in Comics History: The Start of the Image Revolution.”

ComicsAlliance, Townsquare Media, Inc., 1 Feb. 2016, comicsalliance.com/

Reid, Calvin. “Seven Seas Staff Launches Effort to Form Union.” PublishersWeekly, PWxyz,

LLC., 24 May 2022, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/comics/

article/89415-seven-seas-staff-launches-effort-to-form-union.html.

Reid, Calvin. “Seven Seas Voluntarily Recognizes Union.” PublishersWeekly, PWxyz, LLC, 28

Shooter, Jim. “The Jack Kirby Artwork Return Controversy.” JimShooter.com, 1 Apr. 2011,

www.jimshooter.com/2011/04/jack-kirby-artwork-return-controversy.html/.

Thomas, Ian. “A Brief Interview with United Workers of Seven Seas.” The Comics Journal,

Fantagraphics, 9 June 2022, www.tcj.com/a-brief-interview-with-united-workers-of-

Westcott, Kevin. “2023 Digital Media Trends Survey.” Deloitte Insights, 14 Apr. 2023,